Overview

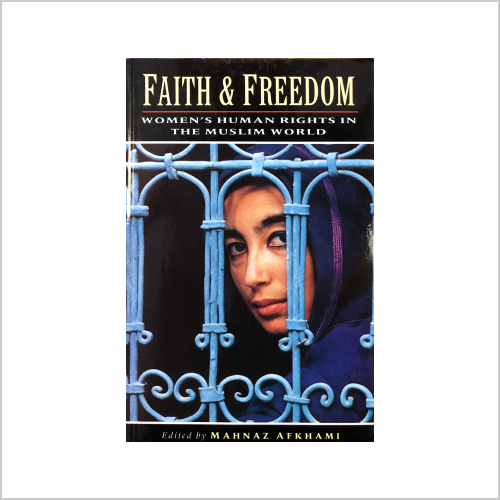

Faith and Freedom: Women’s Human Rights in the Muslim World 1995 / Syracuse University Press and I.B. Tauris / Editor

Over half a billion women live in the Muslim world. Despite the rich complexity of their social, cultural, and ethnic differences, they are often portrayed in monolithic terms. Such stereotyping, fueled by the resurgence of Islamic fundamentalism, has proved detrimental to Muslim women in their campaign for human rights.

This book is the first detailed study to emphasize Muslim women’s rights as human rights and to explore the existing patriarchal structures and processes that present women’s human rights as contradictory to Islam. Academics and activists, most of whom live in the Muslim world, discuss the major issues facing women of the region as they enter the twenty-first century. They demonstrate how the cultural segregation of women, and the monopoly on the interpretation of religious texts held by a select group of male theologians, have resulted in domestic and political violence against women and the suppression of their rights. The contributors focus on ways and means of empowering Muslim women to participate in the general socialization process as well as in implementing and evaluating public policy.

Book Excerpt

Introduction By Mahnaz Afkhami

In Faith and Freedom: Women’s Human Rights in the Muslim World

There are over half a billion women in the Muslim world. They live in vastly different lands, climates, cultures, societies, economies, and polities. Few of them live in a purely traditional environment. For most of them modernity means, above all, conflict – a spectrum of values and forces that compete for their allegiance and beckon them to contradictory ways of looking at themselves and beckon them to contradictory ways of looking at themselves and at the world that surrounds them. The most taxing contradiction they face casts the demands of living in the contemporary world against the requirements of tradition as determined and advanced by the modern Islamist world view. At the center of this conflict is the dilemna of Muslim women’s human rights – whether Muslim women have rights because they are human beings, or whether they have rights because they are Muslim women. Faith and Freedom addresses this issue.

Contemporary Islamist regimes are most lucidly identified, and differentiated from other regimes, by the position they assign to women in the family and in society. For Muslim fundamentalists every domestic issue is negotiable except women’s rights and their position in society. Islamic resurgence, exemplified by movements as varied as Jama’at-i Islami in Pakistan, Ikhwan al-Muslimin in Egypt, the Islamic Republic in Iran, and the Islamic Salvation Front (FIS) in Algeria, insists on singling out women’s relation to society as the supreme test of the authenticity of the Islamic order. The religious fiat, often manifested concurrently as discursive text and naked violence, relies for its legitimacy on a tradition that it assumes invests social structure and mores with an ethic of womanhood appropriate to Islam, symbolized historically by the institutions of andarun and purdah. The ethic and the symbols, however, are becoming increasingly porous as Muslim societies, including a significant number of Muslim women, outgrow and transgress traditional boundaries.

Islamist intransigence forces Muslim women to fight for their rights, openly when they can, subtly when they must. The struggle is multifaceted, at once political, economic, ethical, psychological, and intellectual. It resonates with the mix of values, mores, facts, ambitions, prejudices, ambivalences, uncertainties, and fears that are the stuff of human culture. Above all, it is a casting off of a tradition of subjection.

Islamism reduces this complex, historical struggle to a metaphysical question. It does so by casting society in an idealized Platonic ‘form’ and by equating culture with the dogmatics of religion. This representation is functionally supported by an important strain in contemporary international discourse that takes off from Islam’s assignment of private and public space to women rather than from freedom and equality as the core assumptions appropriate to modern times. Akin to a presumption of guilt in a court of law, this discourse reverses a universally accepted rule. To the extent that Islam, defined and interpreted by traditionalist ‘Muslim’ men, is alowed to determine the context and contour of the debate on women’s human rights, women will be on the losing side of the debate because the conclusion is already contained in the premise and reflected in the process. Arguably, this is the heart of the moral tragedy of Muslim societies in our time.

The Islamist position on women’s human rights is advanced on two levels – one internal, the other external to the Muslim community. Internally, the argument invokes Islam and the inviolability of the text. The formulation is intellectually rigid, but politically well organized and ideologically inter-connected across the Muslim world through chains of ‘traditions,’ clerical fatwas, and periodic government resolutions and legislation. Opposed to it, Muslim women in significant numbers and from all social strata are currently objecting to the fundamentalist interpretation of Islam. The dimensions of the struggle are being defined as Muslim women strive for rights across the globe; what these rights are, how they relate to Islam epistemologically, how they resonate with social and political power in specific Muslim societies, and how strategies that seek to promote them will or should be developed. High on the list are the ways and means of interpreting religious texts: how should women approach the issue, what sort of expertise is needed, how can the issue be bridged to grassroots leaders, how may the intelligence received from the grassroots be brought to the interpretative process? Scholars and activists are also looking into ways of educating the Muslim political elite: how to identify responsive decision makers, how to communicate reinterpreted text, how to develop criteria for judging the limits of political engagement, how to help executives, legislators, and judges sympathetic to women’s human rights to implement change in the condition of women. They are also searching for appropriate patterns of mobilizing grassroots support, including ways of identifying women leaders at different levels, communicating methods of pressuring political decision makers, and, most important of all, protecting women activists against moral and physical violence. The list, obviously not exhaustive, nevertheless signifies the dynamics of the relationship between women’s human rights, politics, and the Islamic texts.

Externally, the Islamic position meshes with the idea of cultural relativity now in vogue with the West, where relevant arguments are waged for reasons that usually transcend the problem of right in its elemental form. In the West, particularly in academic circles, relativity is often advanced and defended to promote diversity. In its theoretical forms, for example as a post-structuralist critique of positivist (liberal modernization) and Marxist development theories, cultural relativism sometimes suggests that universalist discourses are guilty of reinforcing Western hegemony by demeaning non-Western experience. Whatever other merits or faults of the critique, it insists on free choice and equal access. Islamists, however, use the argument functionally to justify structural impairment of women’s freedom and formal enforcement of women’s inequality. This use of the argument is morally unjust and structurally flawed. As mentioned avove, rather than addressing real evolving societies, Islamists abstract Islam as an esoteric system of historically specific social and political conditions. As a result, they transform the practical issue of women’s historical subjugation in patriarchies, which is a matter of the economic, social, cultural, and political forms power takes as societies evolve, to arcane questions of moral negligence and religious slackness. The argument becomes pernicious when it seeks to portray women who struggle for rights as women who are against Islam, which is their religion and in which they believe. The Islamists confound the issue by positing men’s interpretation of religion for religion itself. This book also deals with this question.

The rise in Muslim women’s awareness of their identity and rights is part of a historical process in which all individuals, men and women, have increasingly appropriated their ‘selves.’ The form of appropriation differs from culture to culture, but the essence is commonly shared. Right is a property of control a women achieves over her person over time. It is an appropriation of individual power and acceptance of personal responsibility. It is to assume an identity that seeks perpetually to authenticate its ‘self’ as responsible subject. As history moves from law (the condition of obeying the framework already given) to right (the condition of acting to establish appropriate frameworks), Muslim women must forge and maintain an identity that is historically adequate, psychologically rewarding, and morally acceptable. The resulting tensions, always difficult to accomodate, are intensified by the division of the world into North and South and the attractions and repulsions engendered by racial, ethnic, religious, and national cleavages and solidarities. The transition from law to right is exacting and probably never complete. The challenge is particularly hard for Muslim women because their historical memory is bound to a host of dogmatically firm but logically questionable ‘traditions’ that emotionally and intellectually infuse and sustain their religion.

When successful, Muslim women’s self-authentication becomes a transcending of history as man’s signature. Specifically, it evokes a vision of reality as a world intercounnected spatially and temporally, where cultures are not distillations of values, mores, and aesthetics invented by some extraordinary people at a golden point in time and inscribed in common memory as deified eternal forms, but living, changing phenomena that trace a people’s evolution and a person’s growth in history. Growth involves interaction with others and consequently transformations that bear the mark of the ‘other.’ For most of the Third World the experience of colonialism led the dialectic of encounter to an intellectual impasse by positing the ‘other’ as the enemy. As so much of the ‘other’ is appropriated in the developmental process, the enemy steals within and the impasse, intellectual and political at first, becomes a pathology of self-denial. Since the future is claimed by the ‘other’, the alternative that remains is a scourge bequeathed by the colonial experience. Muslim women must transcend this experience if they are to accomplish their task of self-authentication. Above all, they should refuse to identify themselves as against the world outside. Rather, they ought to seek to lead in defining its issues and shaping its future.

Rights are also related to the changing properties of political culture – values, beliefs, and aesthetics that have to do with the dispositions of power. Hence, unless a substantial number of women in a community come to believe that they have rights and demand to exercise them, right remains an abstraction. Rights and empowerment are interconnected. On the one hand, rights provide individuals with choice and therefore the possibility of diversity. On the other hand, to strive for rights is ipso facto to be empowered. The process takes different forms and passes through different routes, but whatever the form or the path, it places women in history. The question before us is: how will Muslim women, particularly those among them who can communicate with others, influence events, and make a difference, be empowered to advance the cause of women’s human rights? How can the process be enhanced, facilitated, encouraged? What possibilities exist or can be generated for women activists across the world to help Muslim women solve their problems?

The last point corresponds to the concept of global movement for women’s human rights. At the center of this concept is the idea that the conditions women have in common outrank and outvalue those that set them apart. As historical victims of patriarchy, they are naturally united across history; they must now transcend political and cutural divides that are contemporary effects of traditional patriarchal politics. An important part of the ongoing struggle for women’s human rights is the effort to find ways and means of bringing together women from different cultures to work toward solutions to common human problems. The global movement for women’s human rights, therefore, is not exclusively a women’s project; rather, it brings the women’s rights perspective, which is fundamentally gender-inclusive, to choices that need to be made for a more productive and human future for everyone. This historical necessity provides a reason and an opportunity for women from both South and North to cooperate in defining problems and finding solutions.

Two points deserve mention in this respect. First, because Muslim countries have not been colonial powers, Muslim women, like other women from the South, are in a better position politically to help with a global movement for women’s human rights. Many among them are multicultural, familiar with the West, multilingual, and conversant with international organizations and politics. Their freedom, however, is curtailed by a male-oriented hegemonic social structure at home and by their lack of access to the means of communication domestically and internationally. A consequence of this second point is that even when Muslim women are politically able and psychologically willing to participate in the international discourse on women’s human rights, they are constrained in practice, because they lack access to appropriate international organizations, media, and funding.

Second, international forums have been dominated by women from the North. To provide forums for women whose engagement is necessary for the enrichment of the discourse and success of the project is in the interest of all women and a great contribution to the world movement for women’s human rights. Specifically, this project requires an equitable representation for the women of the South in setting the criteria, providing the context, and assigning values that will guide the global movement for human rights. Muslim women need to focus particularly on constructing a set of images that portray authentically personal and cultural diversities that exist among them and which are ignored, misconceived, or misrepresented in the West. Women from the North can help by mobilizing international support for Muslim women’s struggle, particularly through the use of international media and other means of communication to facilitate interaction between Muslim women and the international community as well as among Muslim women themselves. Fair and reasonable representation of Muslim women in international debate will also help correct a debilitating tendency among Muslim women to stereotype, label, and reject women’s movements in the North despite their vitality, good will, and diversity.

Part I: Women, Islam and Patriarchy

This volume – the first to emphasize Muslim women’s rights as human rights – is organized in two complementary sections. Part I addresses the patriarchal structures and processes that present women’s human rights as contradictory to Islam. It discusses the importance of Islam for Muslim women, the anti-woman bias in male creation and interpretation of Islamic texts throughout history, and the need to reinterpret these texts in light of the humane and egalitarian spirit of Islam as distinct from its rendition by its male guardians. It examines how social and cultural segregation of women, contradictory and conflicting legal codes, and the monopoly held by a select group of male theologians on interpretation of religious texts result in domestic and political violence against women and in suppression of their rights. It also focuses on ways and means of empowering Muslim women to participate in the general socialization process as well as in making, implementing, and evaluating public policy.

The general framework for Part I is exemplified by Deniz Kandiyoti’s critique of some of the central assumptions behind the ongoing debates about Muslim women’s rights. noting the recent changed in the climate of opinion on the concept of rights, Kandiyoti makes three analytical interventions. The first demonstrates the politically contingent nature of the relationship between Islam and women’s rights from the post-colonial state-building era to the present. The second analyzes the interplay of local and international agendas and some of their contradictory consequences for women’s movements and rights. The third evaluates the impact of post-modern discourses on ‘difference’ and the multi-culturalism debate in the West on our understanding of rights and coalition-building in Muslim societies. The text concludes by reviewing the difficulties of developing a feminist agenda that accomodates diversity and difference without undermining the legal and ethical grounds upon which the right to difference itself can be upheld.

Fatima Mernissi follows by suggesting that much that comes out of the West about Islam and Muslim societies reflects fantasy masquerading as liberal rationality rather than actual conditions in the Muslim world. She takes to task the proposition that Muslim states are, or have been, ‘religious’ in a way that non-Mulsim states have never been, and therefore separated from non-Muslim experience ontologically. Sunni Islam, in particular, she argues, has never recognized an intermediary between the individual and God. There is no established church in Islam. The caliph wields power as secular ruler. The imam leads prayers, but does not stand vis-à-vis God, the Qur’an, or the Prophet, separate from the rest of the Muslims. That is why the shari’a, the law, has always been of overriding importance in the Muslim world. Two important points follow: (1) tuned to the law, Muslim societies are historically and structurally receptive to democracy’s motto of ‘government of law and not of men;’ and (2) not being separated by an intermediary from their God and His Prophet, Muslims can, in principle, interpret the law and render it current by ordinary individual political intervention. Mernissi wonders at how liberal Western powers that are dedicated to individual human rights cuddle up with modern oil-producing ‘caliphs’ who use secular means to destroy rights by falsely appealing to religion.

Abdullah An-Na’im addresses the nature and implication of the dichotomy between religious and secular discourse on the rights of women in Islamic societies. He argues that although this dichotomy is somewhat false and often exaggerated, nevertheless it can have serious consequences for the human rights of women in these societies. He calls on human rights advocates in Muslim societies to take religious discourse seriously and to seek and articulate Islamic justifications for the rights of women. He calls for diversity and plurality of religious as well as secular advocacy strategies.

Bouthaina Shaaban discusses different interpretations in Islam of the Qur’anic verses about women, their rights and duties. Women, she argues, have been marginalized and kept out of the main stream of Islamic Studies. An example is Nazira Zin al-Din, whose two books of interpretation of the Qur’anic texts about women, al-Sufur wa’l-hijab and al-Fatat wa’l-shiukh, published about 70 years ago caused a storm that resounded in many parts of the glob. Shaaban recreates in some detail Zin al-Din’s position on various Qur’anic texts and her arguments on the affinity between the text fairly interpreted and women’s human rights. She describes how Zin al-Din stood her ground, using unimpeachable sources and inimitable logic to answer her critics and enemies. Subsequent Muslim scholars who concur with her interpretations of the Qur’an and her reading of the hadith, however, have failed to mention Zin al-Din or build on her work, thus, inadvertently, helping the opponents of women’s human rights and equality. Zin al-Din’s contemporary ulama engaged in serious intellectual debate with her. There was no threat of violence or accusation of apostasy. Shaaban wonders what would have happened to her if she had lived in the last decades of our century.

Farida Shaheed examines the contextual constraints that shape women’s strategies for survival and well-being in the Muslim world, the negative implications of increasingy active politico-religious groups seeking political power, and the way in which networking can support women’s struggle for change. Using examples from Pakistan and other Muslim societies, she argues that the struggle for change is hampered by women’s lack of knowledge of exisitng statutory laws and their sources, and a fear of being ostracized if they oppose their community’s definition of ‘Muslim’ womanhood. Women’s networks, she argues, can contribute to change through non-hierarchical linkages, providing women with direct access to a wealth of alternative definitions of womanhood, breaking their isolation, and creating the support mechanisms that enable women to alter their lives. The very fluidity of the network structures challenges the dichotomous choices which both the politico-religious groups and some feminist analyses present to women, placing them in an either/or situation which fails to reflect the complexity and diversity of their everyday lives.

In the last chapter of this part Ann Elizabeth Mayer examines how certain spokespersons for different regimes and religions are currently posing as supporters of women’s rights while, at the same time, pursuing policies that are inimical to women’s rights and that are designed to preserve traditional patterns of discrimination. She assesses the common themes in the rhetoric on women’s rights – that there are certain sacred laws or laws of nature, which men are powerless to alter, that supersede international human rights and therefore must be adhered to. Comparing the rhetoric used by opponents of women’s equality in Muslim countries, the Us, and the Vatican, she demonstrates that all of them define women’s equality so as to accomodate these supposedly compelling sacred laws or laws of nature. These definitions of equality thereby deviate from the standard of full equality for women mandated by the United Nations Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), even as any intent to discriminate is being piously disavowed. Mayer labels this phenomenon ‘the new world hypocrisy,’ and, by showing the cross-cultural similarities in the strategies of opponents of women’s rights in Muslim countries and in the West, she shows that Islam presents no unique obstacle to women’s rights.

Part II: Women and Violence – Selected Cases

In Part II the book presents concrete examples to demonstrate the kind, nature, and intensity of problems women face in contemporary Muslim societies. The stories generally corroborate Anne Mayer’s thesis that Muslim women’s predicament is significantly exacerbated by government hypocrisy. The shari’a is the shield behind which the political ruler and the fundamentalis leader corroborate to check women’s impulse to freedom and equality. In all cases women must endure violence and struggle againts odds. The shari’a, however, can be used to constrain as well as expand rights, depending on the conditions of the society and the orientation of the political elite. The odds are almost insuperable in a country like Saudi Arabia, the dangers daunting in Pakistan and quite lethal in Algeria and Afghanistan. Nevertheless, everywhere women fight for their rights and in some cases, for example in Jordan, they win.

In Saudi Arabia, Eleanor Abdella Doumato states, positions on human rights in public discussion and official legal opinion are always validated by reference to the shari’a. The shari’a, however, is in many respects ambiguous, and therefore opposing political, religious, and social views can all be validated with reference to the same body of Islamic law. Similarly, when it comes to women’s rights, the shari’a can be and is used to constrict rights for women as well as to expand them.

Interpretations of women’s rights in the shari’a are influenced by cultural understandings about women’s limited capabilities and the centrality of women’s role in the family. With economic development, mass education, and the intrusion of global media, however, these understandings are changing. Doumato observes that despite growing conservatism in some sectors of society, women’s actual achievements in business, arts, and academia are undermining traditional attitudes that allow validation in the shari’a of rules limiting women’s right to work, drive, travel, study, or dress as they please. Thus, while the negative side of the shari’a‘s ambiguity is lack of a meaningful standard for human rights, the shari’a may also be viewed as flexible, capable of accommodating international standards for human rights when government, religious scholars, and society at large are prepared to accept them.

Shahla Haeri discusses the politically motivated rape of specific women affiliated to the Pakistan People’s Party in Karachi in 1991. Haeri argues that ‘political rape’ is an improvization on the theme of ‘feudal honor rape,’ and that the target of humiliation and shame is not necessarily a specific woman, but rather a political rival or an old enemy who is to be avenged. Specifically, in these particular cases the target of humiliation and shame was no other than Benazir Bhutto, who was the leader of the opposiiton in 1991. By raping female members of her party, Benazir Bhutto is ‘raped’ by association. Haeri suggests that, in its modern context, political rape is tacitly legitimated by the state. The idea is well corroborated by the experience of thousands of refugee women across the world and needs to be studied further in non-refugee conditions in other countries.

Sima Wali highlights the Afghan women refugees’ plight as a case study of the causes and conditions of displacement of women in general and Muslim women in particular. She notes that a significant proportion of refugees, both those who have crossed international borders and those who have not, have fled from or sought asylum in Muslim socities, a great majority of them women and their children. Refugee women and children must rely on host countries, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, and their international community for protection. In most cases, however, the protection is either non-existent or inadequate. In the Muslim world, refugee women and girls suffer doubly – as displaced persons and as women – since male-dominated host countries subject them additionally to repressive social norms and practices. Wali points to the widespread practice of rape as a weapon of war, which supports Haeri’s account of rape as a political act. She pleads for further attention by the international community and relevant international organizations to the problems of refugee women and children both in host countries and in the process of return and repatriation.

Karima Bennoune details violence against Algerian women by fundamentalist armed groups during the last seven years. She argues that these attacks did not begin in 1992 with the cancellation of th elections, but are rather tied to the fundamentalist social project for Algeria. Bennoune looks also at ways in which women have responded to the campaign againts them and how thei interpret its meanings. The Algerian situation may be a defining moment for the cause of women across the Middle East. Algerian women have enjoyed rights and had participated widely in Algeria’s war of independence and, to a lesser extent, in subsequent Algerian politics.

In the last chapter of the volume, Nancy Gallagher discusses Toujan al-Faisal’s campaign, and final victory, in the two most recent Jordanian elections. Faisal’s story, which Gallagher places in the wider context of feminism, Islamism, and democratization in the Middle East, is encouraging for women everywhere. On 8 November 1989, Jordan held elections for the first time since the imposition of martial law during the June War of 1967. Of the 650 candidates who stood for 80 seats, twelve were women. One of the twelve, a journalist named Toujan al-Faisal, was a prominent women’s rights activist noted for her television program which dealt with such topics as child abuse and wife beating. As part of her campaign, she published an articled entitled ‘They insult us and we elect them’ in Jordan’s leading newspaper (the article appears in the appending to this volume). In November 1989 two religious leaders filed charges of apostasy against her. Citing the newspaper article, the plaintiffs asked the Islamic court to charge her with apostasy, to divorce her from her husband, to remove her children from her custody, and to grant immunity to anyone shedding her blood. The case created an enormous controversy which illuminated deep-seated social and cultural conflicts that are gaining in political importance throughout the Muslim world. While the case continued, all twelve women were defeated in the elections. Rather surprisingly, 20 of the Muslim Brothers’ 26 candidates were elected, and 12 other fundamentalists were also elected, even to several Christian seats. The case continued into the following year when the qadi (judge) of the South Amman Shari’a Court found al-Faisal innocent of all charges. On 8 November 1993, al-Faisal won election to parliament, becoming the first and only woman to serve in parliament in Jordan.

Copyright © Mahnaz Afkhami

Book Reviews

Reviews:

- Into battle with the mullahs / The Sunday Times October 1, 1995 / Susha Guppy

- Tolerable Intolerance? Silence on Attacks on Women by Fundamentalists / Contention: Debates in Society, Culture, and Science Vol.5, No.3 Spring 1996 / Beth Baron

- Al Raida Volume XIII, No.73 Spring 1996 / Nathalie Sirois

- British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies Volume 23 Number 1 May 1996 / Haya al-Mughni

- Development in Practice, Volume 6, Number 3, August 1996 / Haleh Afshah

- Foreign Affairs Spring 1996

- Iran Khabar Vol. 2, No.33 Continuous Issue 85 September 29, 1995 (In Persian)

- Middle East Studies Association Bulletin Volume 30 Number 1 July 1996 / Mary Ann Tétreault

- The Journal of the Society for Iranian Studies Volume 30 Numbers 1-2 Winter/Spring 1997 / Shiva Balaghi

Book Endorsement & Praise

“A gripping combination of serious scholarship and popularising… Their insights from political economy are combined with psychological and sociological models of gender relations, illuminating the ugly and frequently violent gender politics of fundamentalist movements.” — Mary Ann Tétreault, MESA Bulletin 30 1996

“In the opening chapter of the book, Afkhami forcefully and eloquently elucidates the problem women face in the contemporary Muslim world.” — Foreign Affairs, 1996

Memorable Quotes

“Tuned to the law, Muslim societies are historically and structurally receptive to democracy’s motto of ‘government of law not of men’ “.

“The conditions women have in common outrank and outvalue those that set them apart.”

“For most of the Third World the experience of colonialism led the dialectic of encounter to an intellectual impasse by positing the ‘other’ as the enemy. As so much of the ‘other’ is appropriated in the developmental process, the enemy steals within and the impasse, intellectual and political at first, becomes a pathology of self-denial. Since the future is claimed by the ‘other’, the alternative that remains is the irredeemable past. In this sense, Islamic traditionism is a scourge bequeathed by the colonial experience.”

“Rights and empowerment are interconnected: unless a substantial number of women in a community come to believe that they have rights and demand to exercise them, right remains an abstraction.”

“For Muslim fundamentalists every domestic issue is negotiable except women’s rights and their position in society. Islamist resurgence … insists on singling out women’s rights are a Western imposition that impinges on Islamic culture and religion; and they label Muslim women who struggle for these rights as enemies of Islam.”