Overview

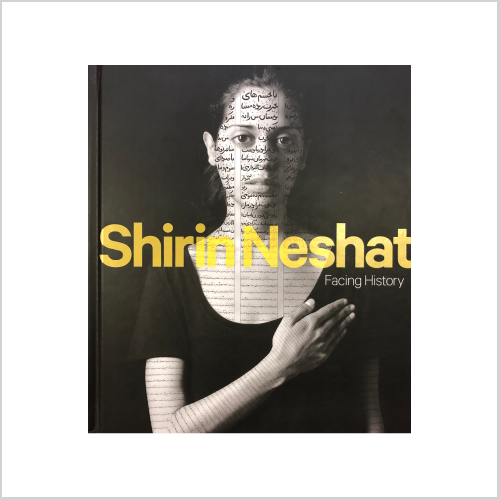

Shirin Neshat: Facing History

Edited by Melissa Chiu and Melissa Ho

Publisher: Smithsonian Books/ Washington D.C./ Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden (2015)

In her mesmerizing films and photographs, Shirin Neshat (Iranian-American, b. 1957, Qazvin) examines the nuances of power and identity in the Islamic world–particularly in her native country of Iran, where she lived until 1975. Shirin Neshat: Facing History is the companion volume to the Smithsonian’s Hirshhorn Museum exhibition of the same name. This beautiful volume presents an array of Neshat’s most compelling works and illuminates the points at which cultural and political events have inflected her artistic practice. Included are the “Women of Allah” photographs that catapulted the artist to international acclaim in the 1990s; lyrical video installations that immerse the viewer in imagery and sound; and the photographic series “The Book of Kings”–including its latest chapter, Our House Is on Fire, created in the aftermath of the recent Egyptian revolution. Hirshhorn curator Melissa Ho provides an introduction to Neshat’s deeply humanistic art, and executive director of the Foundation for Iranian Studies Mahnaz Afkhami contributes a cultural and political history of Iran to contextualize Neshat’s work. Commenting on freedom and loss, the art of Shirin Neshat is at once personal, political, and allegorical, and this book is a testament to its enduring power.

Book Excerpt

“Sunlight, Open Windows, and Fresh Air”: The Struggle for Women’s Rights in Iran

By Mahnaz Afkhami

On the day in 1976 that I moved into my new office in the Prime Ministry building in Tehran as Iran’s first-ever minister for women’s affairs and only the second woman in the world to hold such a position, I sat at my desk for a moment, awed by the task ahead of me and humbled by the great expectations of my colleagues at the Women’s Organization of Iran. On the wall, framed in antique gold, I had hung three poems of Iran’s feminist poets, in beautiful calligraphy by Reza Mafi, an artist whose delicate yet bold lines showed his understanding of and reverence for the women’s words.

Life in Iran is imbued with poetry, so it was not unusual for a new member of the cabinet to display poems in her office. As children we are educated, advised, and guided by poetry that is recited by our parents, offered in our schoolbooks, and integrated into our artistic productions. Our games are often centered on the recollection of poems. Our visual artists often use poems as subject or as medium– and Shirin Neshat’s work is a living example of the potency of using words as image.

Conscious of the enormity of the challenge of my new position, I found the inspiration in the words of these pioneering women poets both comforting and encouraging. Rereading the short quotes from their work in the graceful calligraphy, I could see at a glance the trajectory of the women’s movement through a century of contradiction and struggle.

The poems on my wall were by Parvin Etesami, Forough Farrokhzad, and Tahereh Saffarzadeh, women whose lives spanned a century of Iranian history. Etesami was born at the dawn of the twentieth century, in 1907, during Iran’s Constitutional Revolution (1905-1911), and died in 1941. She spoke of women’s helplessness, isolation, and invisibility and especially of their being deprived of knowledge. Farrokhzad’s short but productive life spanned the mid-twentieth century (1935-1967), when Iranian women gained the right to vote and also gained considerable rights in their personal lives through the family protection laws that they themselves had sponsored and passed as members of parliament. Her poetry addressed the often unspoken taboos and limitations that governed the emotional life of women. Farrokhzad sought the right over her own body, the choice to take joy in full, wholesome, and uncensored sensual experience. Saffarzadeh (1936-2008) began her work with a vital search to connect the best of Iran’s spiritual quest with the modern world’s emphasis on individual choice and personal freedom.

Etesami, empowered by her own unusual education and supported and encouraged by her enlightened father, clearly saw and was appalled by the subordination and invisibility of Iranian women and the apathy that was their underlying cause. A little more than two decades after the Constitutional Revolution had paved the way for the nation to turn from the lethargy, isolation, and ignorance of the previous century and look to the world that was moving swiftly along the path of modernity, she wrote:

A woman in Iran was not a citizen.

She struggled through dark and distressing days.

She lived and died in isolation.

What was she then if not a prisoner?

In the courts of justice no witness defended her

To the school of learning she was not admitted.

(“Zan dar Iran” [Woman in Iran], 1936)

Farrokhzad was a child of the mid-twentieth century. During her formative years, many qomen no longer veiled themselves, and women and men studied, socialized, and worked together. But traditional taboos on women’s freedoms were still intact and upheld in the name of morality and chastity. Farrokhzad’s bold approach to love and life, as well as her openness and pride in her own capacity for physical as well as intellectual experience, was a revolt against the hypocrisy of the sexual mores that served to subdue and diminish women’s liberty and autonomy:

It’s not about anxious whispers in the dark,

It is about sunlight, open windows, and fresh air

And a furnace wherein useless things are burned

And a world pregnant with new seedlings

And birth and ripening and pride

(“Fath-e bagh” [Conquering the garden], 1960-61)

Saffarzadeh– a Sufi who had honed her writing skills in the United States, delved into Buddhism, and experimented with modern poetry– was initially as adamant as any secular feminist about womn’s independence. She abhorred the materialism and commercialism that had been imported into Iran along with the more essential and productive tools of modernity. She struggled to find that unique balance that still eludes many women and men in the Muslim world as they try to negotiate their spirtual needs and their modern values:

The pure source of Azan

Iis like the puoud hands of a man

That frees my healthy roots,

No longer an island, secluded, distanced,

I move toward a mass prayer.

My abultion is of the dark, smoky air of the street

And my nail-polish no barrier to reaching God

I pray for a miracle

I pray for change

(“Fath Kamel Nist” [Victory is not complete] 1962-63)

—

The 1905-11 Constitutional Revolution awakened Iranians from their isolation and reaffirmed their will to enter the modern world and revitalize their society. The constitution ended Iran’s absolute monarchy and provided for public participation in decision making, with no specific reference to gender. However, the elections that followed excluded c”children, criminals, the insane, and women.” For the next two decades, all matters related to women’s lives remained, as they had in the past, within the purview of the clerics and were handled according to their interpretation of Shari’a law. Literacy among women was rare, and the minimum age of marriage was nine. Women were forbidden from entering the public space unless fully wrapped in a dark shroud that covered their faces and bodies; even then, they were allowed to go to only a handful of accepted destinations and, when walking in public, had to move to the side of the street not occupied by men. Women could not marry, divorce, choose a place of residence, travel, or hold a job without the permission of a male guardian, nor could they have guardianship of their children even after the death of their husband.

But the changing political atmosphere and increasing mobility between Iran and Europe in the 1920s, and after, opened a window to the world outside the country’s borders. Women of Etesami’s generation began encouraging education for women and asserting the importance of women’s role in society. During Reza Shah’s reign (1925-41), development and modernization became the country’s top priorities, and his 1934 visit to Turkey reinforced the concept that the emancipation of women was indispensable to his goals. But he was conflicted on this issue. One of his daughters, Princess Ashraf, wrote that before delivering a major speech on the status of women and their new roles and responsibilities in January 1936, Reza Shah– accompanied by his unveiled wife and daughters– had tears in his eyes. However, his personal emotions did not prevent him from taking on unveiling or from supporting women’s education, both of which were anathema to the religious establishment. The nation’s development projects were now to include free, compulsory elementary education for girls as well as boys; secondary education open to all; and the creation of an advanced university in Tehran. Among the Iranian students sent to European universities at this time were several women who returned and took on leadership roles over the next forty years of the women’s movement.

The path to emancipation, however, was not a smooth one for women. Unveiling was not popular, but the policy prevailed as women increasingly chose to remain unveiled. Numerous journals focused on women were founded and grew in influence; those who established them or argued publily for women’s emancipation were often threatened, censored, and attacked. Fakhrafaq Parsa, founder of the journal Jahane Zanan (The world of women), was sent into exile in 1920; yet she nurtured education and public service in her daughter, Farrokhroo, who became a physician, a teacher, one of the first women elected to Iran’s parliament, and the first woman cabinet minister in the nation’s history. Farrokhroo also, most regrettably, was the first woman political prisoner to be executed publicly by the Islamic Republic of Iran, on the charge of “warring with God and corruption on earth” because she had served the nation’s young women as teacher and minister of education.

Throughout the mid-twentieth century, women in Iran continued to fight for their rights. In the 1930s they formed their first effective associations, and by the 1940s some regulations related to the family were brought into the new civil code: the age of marriage was raised to fifteen for women, and the right to divorce, formerly the sole prerogative of husbands, was extended to women under limited conditions. Iran’s vigorous involvement with the United Nations’ Declaration of Human Rights in 1948 brought home to Iranians the concept that rights are the property of the individual regardless of gender, race, religion or nationality. These newly articulated rights, soon ratified by all UN member states, were adopted by leaders of the Iranian women’s movement. In 1965 women from Iran’s National Committee for the Defense of Human Rights presented a petition to Mohammed Reza Shah Pahlavi advocating for the franchise for women. Although the shah promised to support their cause, he was dissuaded by a threatening letter from the clerics. This testifies not only to the power of the clerics but also of their supporters in the bazaar, among the landed gentry, and throughout the ranks of the patriarchal society.

Nonetheless, the struggle continued. In 1956 a group of younger professionals, mostly teachers, led by Mehrangiz Dowlatshahi, established the New Path Society, which focused on gaining the franchise for women. In 1957 fourteen women’s organizations joined to create the Organization for Cooperation of Women’s Associations, which soon was reorganized as the High Council of Women’s Organizations of Iran. The High Council initiated an extensive advocacy campaign for women’s enfranchisement, and the New Path Society prepared a prototype bill on women in the family that did not conflcit with Islam and placed this on the High Council’s agenda. Women’s status being a barometer of clerical influence in state affairs, the clerics responded vigorously. In October 1962, at the High Council’s urging, Prime Minister Amir Asadollah Alam announced that local elections scheduled for early 1963 would be held under a new law that did not prohibit women’s participation; however, strong pressure from the Ulama forced him to exclude women. On January 7, 1963, Women’s Human Rights Day, women’s organizations issued statements, staged sit-ins, and organized a one-day strike in protest.

On January 9, 1963, the shah introduced a six-point program of reform, known as the White Revolution, which was approved in a national referendum. The plan included land reform and the extension of the franchise to women– both anathema to the clerics: land reform had a financial impact on the ayatollahs’ authority, but women’s participation in society was an even greater threat, since it struck at the heart of hierarchical, patriarchal family and community structures.

In June 1963, during the holy month of Moharram, Ayatollah Khomeini called for demonstrations against the two articles and issued a fatwa calling women’s participation in politics tantamount to prostitution and against Shari’a law. Prime Minister Alam called out the armed forces to stop the large demonstrations, and Komeini was detained and eventually exiled.

Despite ongoing extremist threats and violence, women marched in Tehran in support of their participation in the September 1963 elections. For the first time in Iranian history, women participated as both voters and candidates in the elections for the Majlis, or the lower house of the parliament. Six women leaders with long histories of activism were elected to the Majlis, and two were appointed Iran’s first female senators. Once in parliament, these women became a lobbying force for the family law draft that the New Path Society had placed on the High Council’s agenda. In the lower house, two female legislators sponsored the proposal.

The bill was debated for years in various committees but not formally introduced in the Majlis, since the majority party was worried about clerical reaction. As the Majlis debate was underway, Senator Mehrangiz Manuchehrian proposed a daring, almost revolutionary bill in the senate that guaranteed “full and complete equality of men and women, including equality in marriage, guardianship of the child, employment and woman’s right to employment free of the required husband’s approval, and also equality in the right and condition of divorce, inheritance, and all other social, economic and civil matters.” Although her sweeping propositions had no chance of being adopted, they helped the Majlis bill, which was not as radical, to be adopted shortly thereafter, in 1967. The law, significantly amended and fortified in 1975, placed Iran in a leadership position on women’s rights throughout the region.

The pace of change for the status of women in Iran continued unabated. In 1967 a massive, government supported family planning program gave women the opportunity to choose the timing of their childbearing and size of their families. The following year, Farrokhroo Parsa, one of the first women parliamentarians, was appointed minister of education, Iran’s first female cabinet member. The Majlis passed a law that allowed female high school graduates to join the armed forces’ health and literacy corps, sending scores of young women in uniform to rural and less developed urban areas to teach literacy, deliver elementary health services, and advise on agricultural projects. This gave young women credibility and authority at the grassroots level in areas of immediate interest to the population. The following year, for the first time in Iran’s history, five women– including future Nobel Peace Prize laureate Shirin Ebadi– were appointed judges.

In 1966, as women’s status rose and the possibilities for women’s participation in the nation’s cultural, social, and economic life grew, women activists in the High Council convened a 5,000 member national congress, discussed their issues, and created a more structured organization: the Women’s Organization of Iran (WOI). The WOI soon expanded across Iran. It devised an experience-based program-development policy and learned through dialogue at the grassroots level to focus on women’s expressed needs. Women consistently identified “economic independence” as the underlying requirement for all other aspects of their autonomy and self-determination, so the WOI developed a program for women’s empowerment and self-reliance focused on literacy and vocational-training classes, supported by on-site child-care facilities, job and legal counseling, and family-planning information. By 1978 the WOI had 349 branches and 113 training centers in low-income areas of cities and rural communities throughout Iran, with nearly 1 million women participating in WOI centers and activities annually.

To gain international support for its domestic activities, the WOI interacted not only with Iranian policy-makers, but also with women leaders and organizations in other countries as well as with relevant UN agencies. In 1974 the WOI invited Helvi Sipila, the UN’s first female assistant secretary general, to visit Iran and speak with women leaders and activists. In March 1975 the Iranian delegation presented a working paper to the UN Consultative Committee in New York, which was the starting point for preparing the UN’s World Plan of Action for improving the status of women. The committee used Iran’s working paper in formulating the key concepts and policies and preparing its draft plan for the June 1975 UN World Conference on Women in Mexico City. Iranians also conceptualized and lobbied for — and Iran was designated the site for — two important UN research training, and policy organizations for women that were instrumental to advancing the global women’s movement: the UN Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (ESCAP) Center for Women Development was established in 1977 in Tehran (it was moved to Bangkok after the Islamic Revolution). The creation of the International Research and Training Institute for the Advancement of Women in Iran was approved at the Mexico City conference, and, subsequently, by the UN General Assembly. However, when the final contract with the UN was signed in 1978, the Islamic Revolution was in full sway, so it was established in the Dominican Republic.

Iranians also prepared a draft National Plan of Action based on the findings of twelve thematic seminars in the country’s provinces; it was deliberated and revised through more than 700 local meetings over eighteen months and approved by the cabinet in May 1978. This was perhaps the most important accomplishment of Iranian women’s century-long struggle for equality. The breadth of public involvement in preparing the draft through research and statistical studies, grassroots participation in discussions in local councils and women’s groups, reviews by provincial governors, and, finally, approval by the cabinet was unprecedented. But more important was the implementation plan that established a committee of twelve ministries– including health, labor, education, culture, plan and budget, science and higher education, among others– headed by the prime minister, who reviewed the programs’ progress to ensure women’s participation in each department.

Thus, building a strong national women’s movement at the grassroots level, establishing organized and sophisticated advocacy with governmental and other leaders, and maintaining close communication and interaction with high-level UN leaders significantly empowered Iranian women to achieve many of their goals. On the eve of the Islamic Revolution, nearly 2 million women were gainfully employed in the public and private sectors; 187,928 women were studying in Iran’s universities; of nearly 150,000 women employed by the government, 1,666 occupied managerial positions; and 22 Majlis deputies, two senators, one ambassador, three deputy ministers, one governor, five mayors, and 333 town and city council members were women.

—

In 1977 the shah announced the dawn of an “open political space.” The government declared: “Let the pens write and the tongues speak so that the exchange of thoughts and experiences paves the way to the achievement of the aims of the White Revolution. However, this new policy also opened space for both secular and religious opposition to the government. One of the first events that helped generate a new dynamism for the opposition among the elite was a series of poetry readings — “Ten Nights of Poetry”– at the Goethe Institute in Tehran. Night after night, hundreds of young intellectuals came to hear the protest poems and readings by sixty mostly well-known writers and artists– among them were only three women. The position of the Left at that time was that women’s status was a bourgeois concern that would distract and fragment the movement and that gender disparity was an issue that would automatically be solved once the revolution succeeded.

The three women poets who participated in the readings were Simin Daneshvar, a premier novelist; Batul Maftoun, a little-known poet, and Tahereh Saffarzadeh. At that point Saffarzadeh was still a proponent of openness, freedom, and equality. Within a year, however, as the religious fanatics took over leadership of the opposition and superimposed their narrative on the movement, Saffarzadeh was engulfed in the tumult. As she became the leading female intellectual of the fundamentalist revolutionaries, and later of the Islamic Republic, her once powerful, innovative, and courageous poems of struggle morphed into worshipful odes to not only Ayatollah Khomeini but also the Revolutionary Guards and their “selfless service” to the citizens of Iran. Her earlier, profoundly humanist poetry was only one of the myriad sacrifices at the alter of the twentieth century’s only populist theocracy.

At this early stage of the Islamic Revolution, the dichotomy between those who sought more population participation, freedom of expression, and social leveling of life conditions and those who wanted a return to the religious and traditional cultural conditions of an imagined past was not yet apparent. But not long after the Left-leaning intellectuals’ heady poetry nights had ended, demonstrators began burning theaters, movie houses, and banks, insisting on segregated cafeterias for men and women on university campuses, and calling in bomb threats to WOI centers. For them, such entities symbolized the Westernization that was the cause and the effect of modernization.

In 1978 thousands of Iranian women– many wearing hijab because it was their preferred garb, and many doing so to show their solidarity with the opposition– took to the streets to demand democracy. Over the previous fifty years, they had learned how to organize, mobilize, and demand rights. They had moved from sheltered home to the public space. They had gained the right to vote and to be elected, and once in parliament, they had drafted bills and changed laws, including family laws that controlled every aspect of their lives: marriage, divorce, children, work, travel, and the like. They had built these capacities and gained these rights under an authoritarian system that was committed to economic and social development and, within, that framework, had encouraged gender equality and rights. Now Iranian women also wanted democracy.

On February 1, 1979, Ayatollah Khomeini returned to Iran, and on February 11 the Islamic revolutionaries took power. Khomeini encouraged “sisters” to engage in the revolution to regain their God-given rights and freedoms, and after witnessing their powerful presence during the revolution, he changed his earlier position against the franchise and encouraged women to vote in the referendum that instituted the Islamic Republic. However, even before a new constitution was drafted, he annulled the Family Protection Act, declaring that women could not serve as judge, ordered that women in the workplace must be veiled, and announced that public spaces must be segregated by gender. The following years saw many tragic and tumultuous events, including the taking of the American embassy, the horrendous war with Iraq, and a downward economic spiral; yet the government continued to focus on women’s appearance, movement, behavior, and relationships. The new regime drove women employees to early retirement, closed more than a hundred academic fields to women, banned women from certain jobs, and reduced the minimum age of marriage for women from eighteen to nine.

At the height of the Iran-Iraq War (1980-88), one of the bloodiest conflicts in modern history, Khomeini urged women to help defend the nation. The newly created Society of Al-Zahra in the holy city of Qom called for mass mobilization of women. The devastation of Iran’s infrustration and economy necessitated that women be included in the labor market. Segregation of women helped in some ways by providing duplicate jobs in education, health and other areas. Skilled women had become indispensable since the banning of family planning had doubled the population and throngs of children and young adults required more services; this situation also compelled the government to relaunch the prerevolutionary period’s effective family-planning program.

Denied contact with the outside world, facing internal and external obstacles to travel, and deprived of free access to films, books, and artistic productions from other nations, Iranian women compensated with genuine creativity. Music, theater, and other arts moved underground. Government apathy or hostility drove women to rely on their own energy and capacities and to flourish in various entrepreneurial projects. Women demonstrated in myriad ways that the modernity and rights they had struggled for were not an imported and alien luxury but their own choice that they adapted in their own ways– ways compatible with their culture and history.

During the 1980s “Islamization” took on new momentum. In 1981 Fereshteh Hashemi and Zahra Rahnavard established the Women’s Society of the Islamic Revolution. The new penal code allowed stoning of married women for adultery, assigned a value to women’s “blood” equal to half that of a man’s, and prescribed seventy-four lashes for inadequate veiling. Ayatollah Khomeini issued a fatwa legalizing temporary marriages. A special women’s patrol, the Guardians of Orthodox Islamic Culture, consolidated and enforced the Islamic Republic’s gender policies. The newly organized official women’s groups increased conservative religious women’s participation in politics. Ironically, gender segregation in all public spaces and enforced veiling providing women from traditional backgrounds with a safe space to enter the sociopolitical arena and to come into contact with secular feminists, which exposed them to a new vision of the role of women.

In 1992 Shahla Sherkat, who during the Islamic Revolution had been a conservative religious activist, launched the journal Zanan (Women), around which feminist activist congregated. Over time the journal became increasingly feminist in tone and content and finally was forced to discontinue in 2008. But during the sixteen years of its existence, it provided an excellent venue for original thinking and led to a healthy cooperation and mutual understanding among diverse groups of women. Its reemergence in 2014 is a hopeful development for Iranian women.

Since the end of the Iran-Iraq War women activists have fought valiantly to repel attempts to further reduce their rights and introduce new limitations on their activities, including new bills in the Majlis banning images of women in publications, movies, and other media as “a threat to their dignity” and recommending segregation of all health services. The first bill failed to pass, and the second was deemed unworkable because of lack of personnel to handle the double load of segregated services.

Iranian women have learned to resist peacefully when they can, aggressively when forced– but they never give up. During the 1970s women intellectuals, jurists, writers, and housewives steadily pressed for political change in Iran and quietly, but powerfully, honed their demands and swelled their ranks. Their calls for justice and equality served as a critical undercurrent that shaped the political framework just beneath the surface. In the post revolutionary era, whenever the regime has permitted demonstrations– for example, to increase voter turnout– women have used the opportunity to take their demands to the streets. In 1997 they helped organize the drive that resulted in Mohammad Khatami’s landslide victory.

In 2006 secular organizations and traditional religious groups united and launched the One Million Signatures for the Reform of Family Laws Campaign to eliminate discrimination against women in marriage, divorce, child custody, employment, and the like. Since independent organizations were nearly impossible to register and gatherings and associations were politically dangerous, women gathered in homes to discuss their grievances, aspirations, and strategies. They opted for inclusiveness– veiled and unveiled women coming together. Secular women realized that the religious women were often as independent and courageous as they were. Conservative women saw the justice of the secular activists’ cause. In time these women were able to reach consensus on major issues. The thousands of gatherings and brainstorming sessions evolved into a movement for change focusing on family laws but also touching on many other areas. The resulting One Million Signatures campaign evolved into a highly complex and nuanced sociopolitical and cultural movement that recruited men as well as women.

But the regime struck back. From 2006 to 2008 leaders of the movement were harassed and arrested. Following the uprisings of 2009, every one of the thirty founders of the campaign was arrested and tried for acts against state security, imprisoned, and fined. And although each of these leaders carried a suspended sentence as a sword of Damocles to force her to cease the fight, they and others still persisted. They published pamphlets and recruited volunteers, and they mobilized grassroots support by going door-to-door to explain their goals and ask for signatures, leaving brochures with information about discrimination whether or not the women signed the petition. Simultaneously, they reached out to other civic groups to build a broad coalition that included intellectuals, students and labor movements, and political activists, and they learned to use social networking tools such as text messaging, mass emails, Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube. Before long they had taken their message to the entire region, and then to the world. Leading up to the 2009 presidential elections, the groups lobbied the candidates for ratification of the UN Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, which Iran’s Guardian Council had declared anti-Islamic and all three official candidates had originally rejected. The groups’ power and savvy political strategies resulted in the reform candidates accepting their terms.

During the last two decades Iranian women writers and filmmakers have flourished despite the continuing limitations on their work. Several women directors gained national and international recognition, among them the eighteen-year-old Samira Makhmalbaf, who won the Jury Prize at the 2000 Cannes Film Festival (and plaudits at other international festivals) for her film The Blackboard. Iranian novels and memoirs flourished inside and outside the country. The communication revolution provided opportunities for interaction among Iranian women within Iran and with others around the world.

In 2009 the election of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad (generally viewed as rigged) fueled the Green Movement that brought hundreds of thousands of women and men to the streets and shook the foundations of the Islamic Republic. Women played a prominent role at every level in the movement– from their initial support of reformist candidates to protesting the government’s version of the results. Their quiet and thoughtful community organizing, constituency building, message development, and pioneering use of the Internet were crucial to the scope of the 2009 protests.

While brutal suppression stopped the Green Movement in its tracks, this first major uprising in the Middle East- North Africa region inspired the Arab Spring two years later, a movement that employed similar strategies and, faced with weaker response by the authorities, succeeded where Iran’s had failed. In Iran the One Million Signatures Campaign and the networks within it provided an opportunity for Iranian women to engage in a powerful political movement and hone their skills in creating a culture of democracy within their own ranks. The campaign’s shared vision and pragmatic skills-building will provide a solid foundation for the creation of a future democrat society.

In 2010 the US National Endowment for Democracy awarded its Annual Democracy Award to the Green Movement. Simin Behbahani, Iran’s preemient poet, was invited to receive the award on the movement’s behalf. Behbahani, who as a young girl had been mentored by Parvin Etesami, had written in defense of women’s rights all of her life, including the decades since the Islamic Revolution. Under house arrest, she sent a message to the assembled human rights defenders, activists, and lawmakers at the US Capitol, in which she said:

Let green spring burst forth

Let green flora come alive

Let joy fill the heart of all

Who are grieved by this morbid, ashen fall.

Behbahani died in 2014. The torch she carried passed to the young artists like Shirin Neshat who continue Iran’s long tradition of using poetry, calligraphy, and politics to express their human rights. Artists like Neshat continue to seek and will no doubt find salvation for their country– a country that was once known around the world as “the land of nightingales and roses” and will once again claim that identity.

Mahnaz Afkhami is president and CEO of the Women’s Learning Partnership for Rights, Development, and Peace, and the former Minister for Women’s Affairs of Iran.