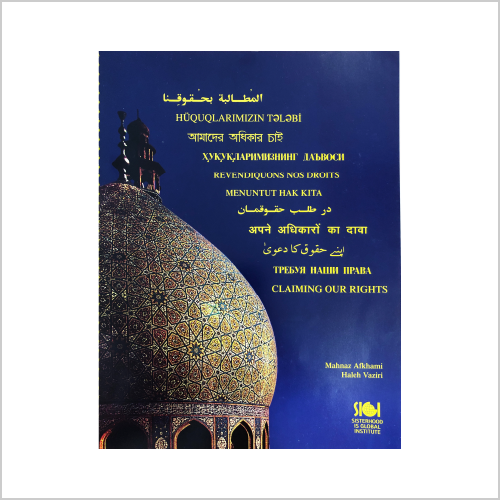

Overview

A Manual for Women’s Human Rights Education in Muslim Societies 1996 / Sisterhood Is Global Institute / Co-authored

Co-authored with Haleh Vaziri; Published in Arabic, Azeri, Bangla, English, Hindi, Malay, Persian, Russian, Urdu and Uzbek.

Read on the Women’s Learning Partnership Website

The introduction to Claiming Our Rights describes the origin of the manual from a series of dialogues among women’s rights leaders, and introduces the manual’s objectives, premises with respect to Islam, education model, and structure. Claiming Our Rights is a manual for women’s human rights education in Muslim societies. It is only when women reclaim their own cultures, interpreting texts and traditions in self-empowering ways, that women may truly claim their rights.

Book Excerpt

In A Manual for Women’s Human Rights Education in Muslim Societies

The idea of a human rights education project for women in Muslim societies originated during a series of meetings, discussions, and conferences held and sponsored by SIGI since 1993. Specifically, SIGI members Mahnaz Afkhami, Fatima Mernissi, and Nawal Saadawi, as well as several women scholars from Muslim societies, discussed the idea at the 1993 Middle East Studies Association’s women’s human rights meeting at Duke University in North Carolina.

Subsequently, at several SIGI-sponsored conferences-including the conference on “Religion, Culture, and Women’s Human Rights in the Muslim World” held in Washington, DC in September 1994-participants emphasized the need for taking the internationally recognized human rights concepts to Muslim women at the grass roots level. Participants in the Commission on the Status of Women meetings of March 1994 and 1995 reiterated the same point. Invariably, women underscored the lack of material employing culturally relevant language to convey the message of international human rights documents to Muslim women. At the SIGI steering committee meeting of May 12, 1995 in Washington, DC, members stressed the need to develop models that could use indigenous ideas, concepts, myths, and idioms to explain the rights contained in international documents. Then, at the Aspen Institute Conference in Berlin, on May 21-24, 1995, representatives from 16 Muslim countries debated strategies for improving women’s human rights in their regions. They identified the production of material using indigenous concepts and ideas to support international rights documents and the training of national and regional intermediate leaders as projects of the highest priority. SIGI then undertook to produce a manual based on a model that would approximate the requirements the participants in these conferences had identified. The present volume is the outcome. Because prevailing economic, social, cultural, and political conditions affect the patterns of information flow, individual behavior, and community interaction, the resulting volume, Claiming Our Rights: A Manual for Women’s Human Rights Education in Muslim Societies, was based on a multidimensional, dialogical, flexible and user friendly model. The manual’s objectives, premises, model, and structure are explained below.

The Manual’s Objectives

The purpose of this human rights education manual is to facilitate transmission of the universal human rights concepts inscribed in the major international documents to grass roots populations in Muslim societies. The manual seeks to enable grass roots populations to convey universal concepts in association with indigenous ideas, traditions, myths, and texts rendered in local idiom. It aims to empower grassroots women to articulate and demand their human rights through interactive communication at home and through the political process in the community and society.

Major International Sources of Women’s Rights

We have used documents for this study that are particularly relevant to women’s human rights, including: the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948), the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (1966), the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (1966), the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (1979), the Declaration on the Elimination of Violence Against Women (1993), and the Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action adopted by the World Conference on Human Rights (1994). The first four of these documents are appended to this manual.

The Mission Statement to the final Platform for Action of the Fourth World Conference on Women (Beijing, 1995) summarized the main points of these documents. The first and second articles of the Mission Statement read:

- The Platform for Action is an agenda for women’s empowerment. It aims at accelerating the implementation of the Nairobi Forward-looking Strategies for the Advancement of Women – and at removing all the obstacles to women’s active participation in all spheres of public and private life through a full and equal share in economic, social, cultural and political decision-making. This means that the principle of shared power and responsibility should be established between women and men at home, in the workplace and in the wider national and international communities. Equality between women and men is a matter of human rights and a condition for social justice and is also a necessary and fundamental prerequisite for equality, development and peace. A transformed partnership based on equality between women and men is a condition for people-centered sustainable development. A sustained and long-term commitment is essential, so that women and men can work together for themselves, for their children and for society to meet the challenges of the twenty first century.

- The Platform for Action reaffirms the fundamental principle set forth in the Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action, adopted by the World Conference on Human Rights, that the human rights of women and of the girl child are an inalienable, integral and indivisible part of universal human rights. As an agenda for action, the Platform seeks to promote and protect the full enjoyment of all human rights and the fundamental freedoms of all women throughout their life cycle.

The Platform for Action identified 12 focus areas for the improvement of women’s human rights: poverty, education, health, violence against women, effects of armed conflict, economic structures and politics, inequality of men and women in decision-making, gender equality, women’s human rights, media, environment, and the girl child. The Conference emphasized that the objective of a reasonably efficient national human rights policy must be to operationalize the rights identified, articulated, and guaranteed in the international documents within particular political, economic, and cultural settings. This formulation implies that governments are committed to the promotion of women’s human rights in their respective societies. When this is not the case, the difficulties that may exist in the transmission of universal human rights to the grassroots are exacerbated.

Major Premises

Many Muslims believe that Islam contains the essentials of human rights and that its content, as God’s revelation, is superior to ordinary law. Consequently, human rights documents must be presented in dialogue with .Islamic tenets if they are to succeed in Muslim societies. Thus, a promising human rights education model should examine the argument that universal human rights contradict Islam.

A central premise of the human rights education model presented here is that universal human rights are consonant with the spirit of Islam. This foundational statement is based on the following propositions:

- The Qur’an as the word of God is eternal, infinite, and mystical, understood in its eternal and infinite function by the Prophet only. All other mortals have received and understood it according to their human gifts. The religious experience-the experience of the “Word of God”-therefore, is by definition a personal experience, whereas obeying “religious law” the shari’a rendered as fiqh in the major schools of jurisprudence-is obedience to manmade law.

- The shari’a-the rules which have governed Muslim societies throughout the centuries-is historically determined and temporally situated because it has had to be rendered understandable to each age and community by reference to the needs of that age and community.

- Because human society has been organized hierarchically and patriarchally across the ages, the shari’a, like all other religiously inspired laws, reflects the social realities specific to that age. Consequently, the ‘ulama have interpreted the Qur’an as well as the sunna to reflect the historical reality they have belonged to and favored. The interpreters of the Qur’an and the sunna have been able to offer different interpretations during different epochs precisely because the original “Word” is infinite in depth and scope. Hence, it is applicable to innumerable circumstances and is able to define evolving conditions infinitely.

- There are specific verses in the Qur’an attesting that God foresees human limitation and consequently enjoins the Prophet not to force human beings in religious matters. Where the Qur’an clearly states that some social policy must be followed, the statement is, by implication, always bound to the requirements of time and space.

- The moral impulse of the “Word”-its eternal thrust-is toward equality for all. All instances of inequality are time and space dependent. Since the Qur’an values the human person as God’s creation, it also values the individual person’s right to live in equality with other persons under God.

- These points produce a moral imperative to achieve gender equality within Islam’s ethical compass. Thus, the political system must promote gender equality.

- The Qur’an and the sunna substantiate these positions, provided that one moves significantly outside the traditional epistemology of Islamic shari’a. The Islamic Gnostic tradition directly supports them.

Theoretical Framework of the Model

Education models are communications models. Analytically, such models require a communicator, a medium, a message, and an audience. Interactively, the components mesh: the communicator and the audience become participants in the production and interpretation of the message as well as in the construction and validation of the medium. When successful, the process leads to constructive discourse. A successful communications model is always open-ended. Rather than aiming ‘at incontrovertible truths, it produces dialogical frames where ideas can be freely discussed and analyzed. Thus, it helps individuals become participants in defining the relevance and validity of ideas regardless of their source or age. The appropriate function of a human rights education model, therefore, is to promote “rights” by facilitating individuals’ participation in the definition of law or truth. In this sense, a successful education model problematizes and politicizes concepts, designing and defining freedom as it unfolds. This is what the present model hopes to do.

Communicator Transmission of a women’s human rights message may begin at any individual or organizational locus. The most natural places for it, however, are women’s organizations, human rights organizations, and, where possible, appropriate government agencies. In this model, we assume that the originator and the facilitator will be the existing or future women’s organizations aided by local and international women’s rights advocates and human rights organizations. In many cases, we expect that the state or particular government agencies will assist.

Women’s organizations in Muslim societies are mostly composed of and led by women in middle positions in public and private organizations, particularly women teachers in intermediate and higher education. Since they can reach a wide audience of young women and men, these women are favorably placed to promote human rights concepts. Many of them are well educated in values that transcend parochial boundaries. More importantly, their position as teachers and role models for the youth give them moral authority and social acceptability. Furthermore, communicating is the very essence of their profession, an important advantage in constrained political and cultural conditions. Human rights groups work to defend the rights enjoyed by individuals under existing constitutions and to promote rights not yet achieved. Although they may not possess the direct means of person-to-person communication available to women’s organizations, they are, in theory, better equipped and usually better connected to the media.

When in the past Muslim states have supported women’s human rights, they have usually done so as a component of their modernization policies. However, the resurgence of militant fundamentalism has caused a decrease in or reversal of this support in recent years. Hence, mobilizing the state in support of women’s human rights is imperative if the goals of the Platform for Action are to be met. When fundamentalists do not directly control states, a human rights education model should help women’s organizations and human rights groups empower the state to confront fundamentalism by opening political space to women, enacting affirmative action, and proposing legal reform. To achieve these goals, women’s advocacy groups must engage in networking and building constituencies at both national and international levels. These activities, in turn, require a reasonably free and open political environment. The model, therefore, is geared to ideas, structures, and actions that enhance democracy and promote civil society.

Audience This model is based on interaction, reciprocity of roles, and exchange of positions between communicators and their audiences. It does not aim to teach a particular truth but rather to establish dialogue. This model foresees communication among equals. The audience varies depending on the purpose of communication. It may be a government agency, a religious group, a village gathering, women in a workshop, or family members. The preponderant focus of rights communications, however, must be the youth. The young are not only more receptive intellectually and ethically, but as students, they are also more accessible. They constitute a significant majority of the population in the target societies. They are the future leaders. Given the criteria of human rights education, their participation in the discussion of rights, in and of itself, is a strong impetus to the development and democratization of civil society.

The model assumes that whenever a sustained dialogical situation develops, rights are promoted regardless of the content of the dialogue. For example, only when all sides have achieved a significant degree of consciousness of rights can a young woman in a Middle Eastern village or small town maintain an ongoing conversation about her rights as an individual in matters of love and marriage with her father, brother, or teacher.

Medium The medium is multifaceted, including the mass media, formal and informal organizations, and groups and individuals. The more extensive and numerous the communications channels, the more successful the human rights project. A good medium allows for dialogue. But even a one-way channel, such as radio or television, is better than no channel at all-even though radio and television are usually controlled by governments that may hold and advocate views which conflict with universal human rights.

The model assumes that most governments officially promote rights, even though many define rights in terms of values that may diverge with universal rights concepts. Still, when governments are forced to defend their vision of rights, they do so in recognition of a social consciousness they feel they must address. This makes the mass media, which is generally controlled by governments, a vehicle of rights. Thus, rights advocates must either convey their vision of rights on radio and TV broadcasts directly, or promote it indirectly by pressuring the government and other adversaries into defensive positions as often as possible. The globalization of communications technology-radio, TV satellites, the Internet, etc.-has enabled international rights organizations, states, and the corporations that control the international media to play an overwhelming role in transmitting the rights message.

In this model, the primary medium is face-to-face communication. We assume, however, that the facilitator and participants will bring to the dialogue a wealth of knowledge and experience derived from their personal and social circumstances. We also assume that due to the political dimension inherent in any dialogical situation, interpersonal communication will produce not only a new awareness of rights but also a propensity to communicate this awareness through the mass media whenever possible.

Message The model assumes that a message of rights is authentic if it leads to the’ strengthening of a dialogical condition. This means that an efficient message cannot be validated independently of the communicator, the audience, and the medium. An efficient model designs messages that users can operationalize in the existing cultural, political, and technological environments.

As we have stated, all human rights messages in this model proceed from the universal values contained in the international human rights documents. This model will facilitate the problematization of patriarchal values. Individuals will discuss these in relation to the existing conditions on one hand, and to the universal precepts of rights on the other. The operative concepts here are identity and authenticity in a context of freedom and equality. Because individuals must receive and understand the message, the model must attend to the cultural and technological environment of the target population.

As with any collective social good, achieving women’s human rights also requires an understanding of the political process and the importance of organizing for political action. Thus, human rights messages must promote the following activities: constituency building, networking, affirmative action, legal reform, and resistance to extremism.

Copyright © Mahnaz Afkhami

Book Reviews

A Manual on Rights of Women Under Islam/ The New York Times/ Barbara Crossette/ December 29 1996

For several years, an informal group of Muslim women from around the world has met to spur discussion among Muslims everywhere about the rights of women. Now, with the shadow of a repressive Islamic regime in Afghanistan hovering over the debate, the group has produced a manual on the rights of women under Islam.

Intended to be adaptable to a wide range of cultures, the new publication, ”Claiming Our Rights: A Manual for Women’s Human Rights Education in Muslim Societies,” will be tested over the next year in five very different countries: Bangladesh, Jordan, Lebanon, Malaysia and Uzbekistan. The plan is to assemble discussion groups to exchange ideas on the subject. There has already been a quiet trial run among a group of university women in Iran.

”There is a great change in self-awareness among women in Muslim societies,” said Mahnaz Afkhami, executive director of the Sisterhood Is Global Institute, a private organization based in Bethesda, Md. Ms. Af khami directed the effort on the manual, produced with the help of the National Endowment for Democracy and the Ford Foundation.

Sometimes at great risk to themselves, women are making gains, though frequently small and fragile. But developments like the introduction of more egalitarian family laws in North Africa often go unnoticed, Ms. Afkhami said, because militants and fundamentalists dominate contemporary images of Islam.

”This very sound-bite-friendly Islamicist movement doesn’t allow the other side to be heard,” she said in an interview. ”But women are often the center of debate, even in Iran.”

Ms. Afkhami, who was Minister for Women’s Affairs in the Government of the last Shah of Iran, Mohammed Riza Pahlevi, has strong critics among Islamic women because of that. And she is aware that promoting women’s rights from a base outside the Muslim world attracts the criticism that the campaign is Western and alien.

”We are not confrontational,” she said. ”Our manual is Islam-based and not threatening. Our hope is that we can get people to engage in dialogue.”

The manual on women’s rights in Islam — which is being published in Arabic, Bengali, Malay, Persian and Uzbek as well as English — contains instructions for conducting grass-roots discussions. It also includes sometimes provocative passages from the Koran — like those about a husband’s punishment of an ”ill-behaved” wife — and the Hadith, the often-disputed collection of teachings of Mohammed as recorded by religious leaders centuries later. Juxtaposed are texts of major international agreements on human rights, particularly women’s rights, which many Muslim nations have signed.

The book briefly profiles four women it calls ”the first heroines of Islam”: two wives of Mohammed; his daughter Fatima, and Zainab, the sister of a Shiite leader who persuaded a victorious enemy to spare her brother’s life. There is also a sampling of Arab proverbs about women, a bibliography, and the names, addresses and telephone and fax numbers of women’s rights groups throughout the Islamic world.

Women who contributed to the manual brought a range of experiences to bear, Ms. Afkhami said. In Bangladesh, there is an interest in more sophisticated political training at the local level. In Uzbekistan, women are concerned that they will lose rights they enjoyed under Communism. In Malaysia, women’s organizations are engaged in scholarly revision of traditional Muslim laws.

”Give women rights, let them participate — that’s the lesson of Malaysia,” Ms. Afkhami said. ”The spirit of our religion is egalitarian.”

Other Review:

Book Endorsement & Praise

“A manual that, unlike traditional human rights law, reconceives rights as also relevant in religious and cultural spheres, not just in the public sphere.” – Madhavi Sunder, The Yale Law Journal