Overview

Interview with Mahnaz Afkhami, secretary general of Women’s Organization of Iran (WOI), 1970-1978, and Iran’s minister of women’s affairs, 1975-1978. 2003 / Foundation for Iranian Studies / Bethesda, MD Gholam Reza Afkhami, ed.

Iranian women gained significant rights and became considerably more active and effective socially, politically, and economically between 1963 and 1978. Mahnaz Afkhami was secretary general of the Women’s Organization of Iran (WOI), 1970-1978, and Iran’s minister of women’s affairs, 1975-1978. In this book she discusses how women propelled the progress they made in Iran’s patriarchal society, how the government’s worldview, politics, and policies affected their progress, and how relevant to their cause was their presence on the international scene and the use they made of international organizations, treaties, conventions, and declarations. Afkhami’s discourse focuses on the cultural, social, and political challenges Iranian women have had to face, and to overcome, before and after the Islamic revolution.

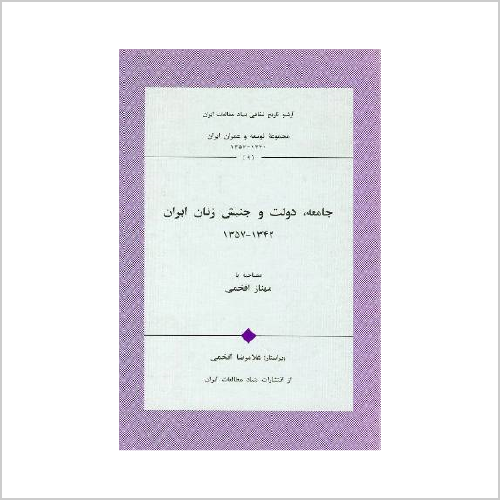

To access the complete volume in Persian, click on its title: Jâme`e, dowlat, va jonbesh-e zanân-e iran, 1342-1357.

Book Reviews

Review: Journal of Middle East Women’s Studies Vol. 1, No. 1 (Winter 2005) / Janet Afary

BOOK REVIEW

“Mahnaz Afkhami: A Memoir” Reviewed by Janet Afary

Afkhami, Gholam Reza. Ed., Jame’eh, Dowlat, va Jonbesh-i

Zanun-e Iran, 1357-1342: Mosahebeh ba Mahnaz Afkhami [Women, State, and Society in Iran 1963-1978: An Interview with Mahnaz Afkhami] Bethesda: Foundation for Iranian Studies, 2003. Pp. IXX + 278.

Mahnaz Afkhami’s memoir, which appears as a series of interviews by Shahla Haeri and Fereshte Noorai and is edited by her husband, Gholam Reza Afkhami, is a moving narrative in Persian that competes with some classics of Middle East women’s studies such as Huda Shaaravi’s Harem Years. Afkhami was head of the Women’s Organization of Iran ( WOI) and the first Minister of Women’s Affairs under the Pahlavi regime. While in exile in the United States after the 1979 Islamic Revolution, Afkhami became one of the founding members of the Sisterhood is Global Institute. In January 2000, she founded the Women’s Learning Partnership for Rights, Development and Peace (WLP).1

On her father’s side, Afkhami belongs to two, dissident social groups within the Iranian elite, the Qajar royal family (1797-1925), which was de- posed by the Pahlavi regime, and the Sheikhi branch of Shicite Islam, which has challenged the authority of the dominant Usülí Shicite clerics since the eighteenth century. Like Shaaravi, Afkhami grew up in the large mansion of her grandparents with 20 to 30 members of her extended family and numer- ous attendants. She has positive memories of what she sees as an idyllic pe- riod when she lived with many cousins and relations and attended a Zorastarian school. Since the family maintained a tolerant and liberal view toward religious practices, she also recalls the joy she felt in practicing Muslimrituals such as the daily prayer or the family gatherings in the months of Ramadan and Muharram.

On her mother’s side, Afkhami belongs to a family of strong and inde- pendent-minded women. In the 1920s, her grandmother left her husband and earned a living as a seamstress in the city of Kerman, in southeast Iran. Afkhamfs mother was no less brave. She left the spacious mansion of her wealthy husband and his extended family in her early thirties and moved to the US in 1955, where she went to college, worked, and raised her three chil- dren by herself (p. 9). Afkhami was fourteen at the time and spent the next ten years in the US, first in Seattle and then in San Francisco, where she at- tended San Francisco State University, and later in Boulder, Colorado, where she received her MA at the University of Colorado. She married her lifetime partner at the age of 17 and raised a son. These were lean financial years for her, and she earned her tuition by working in a five-and-ten-cent store. Her first experience with trade unions comes from this period, when her employer subjected her to a temporary layoff to avoid giving her a Christmas bonus. Afkhami appealed to the relevant branch of the union, Local 1100, and as a result was reinstated. This incident, which she recalls with great excitement in the book, increased her political consciousness and gave her confidence that one could bring about social change through organizing and union activity (p. 15).

Upon her return to Iran in 1967, Afkhami took a teaching job at the National University and within two years became chair of the Department of English. Moved by her students’ interest in negotiating the tensions be- tween modernity and tradition and their earnest attempts to create a space for themselves in society while maintaining their cultural and religious roots, she founded the University Women’s Association. The association soon grew in size and influence and established contact with the WOI. At the time, Prin- cess Ashraf was the honorary president of the WOI and also headed the Ira- nian delegation to the UN. In 1969, Afkhami was included in the Iranian del- egation that accompanied the princess to the General Assembly of the United Nations. Ashraf Pahlavi was favorably impressed by Afkhami’s work at the UN, including a talk she gave on Palestine. Later she offered her the position of the secretary-general of the WOI. Afkhami, who had read the works of De Beauvoir, Betty Friedan, and Kate Millet, decided to take the plunge and work from within the system for gender reform, even though many of her friends and colleagues warned her that the system would not allow her to function independently or achieve a great deal.

In contrast, Afkhami’s younger sister was attending UC Berkley at the time, in the midst of the anti- Vietnam war movement of the 1960s. She became a leader of the Confederation of Iranian students, a large umbrella or- ganization in exile that fought for the overthrow of the Shah. The two sis- ters moved in opposite directions, and they maintained somewhat strained relations in those years.

At the helm of the WOI, Afkhami began a two-pronged approach to identifying the needs and challenges that Iranian women faced. She sought the advice and guidance of a generation of older advocates of women’s rights, individuals such as Farrokhru Parsay, the Minister of Education, whose mother had also been a pioneer feminist in the early twentieth century, and Senator Hajar Tarbiyat, who had been an activist in the turbulent 1940s, when many political parties had openly functioned in Iran. Afkhami has much gratitude for the kindness of these older, more established women. Farrokhru Parsay came to visit her, congratulated her on her new position, and pledged to support WOI programs. But Parsay stated that she was Minister of Edu- cation and not Minister of Women and thereby could include only a limited number of projects related to women in her ministry. Indeed, at the time the very idea of a minister of women seemed quite far fetched to both of them. Dur- ing an official ceremony, Senator Mehrangiz Manouchehrian took Afkhami to the senate lounge and ordered Turkish coffee. Under the half-quizzical guise of reading her future through coffee leaves, she advised her on ways of conducting herself in her new position. Among other things, she recom- mended that Afkhami use the support and connections of Princess Ashraf but “not allow the WOI to become identified with the court or Princess Ashraf” (p. 53), a feat that became impossible, much to Afkhami’s regret.

The second approach Afkhami adopted was to sit with groups of women who were the intended recipients of WOI’s programs and services in various parts of Iran and ask them to identify their priorities and needs. Some of the fascinating parts of the book are about the ways in which the WOFs programs evolved through communication and interaction with the grassroots women who constituted the membership. Educated by the women it mobilized, from peasants and factory workers to urban professionals, WOI focused on eco- nomic self-sufficiency as the overriding purpose of its activities. Around the nucleus of vocational training and literacy classes, which provided job oppor- tunities, a number of other needed services were developed. The opening of these vocational classes quickly proved the necessity for instituting day care centers. Child care led to requests for better health care and birth control. Family planning led to the creation of village courts, where women received advice on divorce, child custody, and other legal matters.

When five or six women organized around women’s issues in a small town or village, they were contacted by the WOI and encouraged to open a branch of the association with about thirty members. Next, elections were held. Seven members were elected to the leadership, which included the po- sition of an executive secretary. Each branch sent a representative to the pro- vincial meeting. There, representatives were elected to take part in the annual general assembly of the organization. The general assembly elected five mem- bers of the central council (out of eleven). The other six were appointed by Princess Ashraf (p. 60). The appointed leaders often included highly educated women and ones from non-Muslim communities. Afkhami explains that since the general membership did not identify with these two groups, if all the del- egates were elected, neither women academics nor minorities would have been represented in the central committee. In this way, and over the years, WOI ended up with a number of outstanding minority leaders including a Jewish educator, Shamsi Hekmat; a Baha’i psychologist, Mehri Rasekh; a Bahai academic, Nikchehreh Mohseni; and a Zoroastrian specialist in cottage indus- tries, Farangis Yeganegi, at a time when orthodox Muslim clerics had de- nounced the participation of non Muslims, especially Jews and Bahais in lead- ership positions (p. 57).

By 1978, the budget of WOI had reached around 50 million tumans (around $400,000), and this amount was collected from sales of textbooks at schools. WOI now made a substantial contribution to the process of devel- opment through skills building and vocational training, health, nutrition, family planning, and environmental protection projects. Its grassroots base, as well as the backing it received from the royal family, turned the organiza- tion into a very powerful institution. In the late 1970s, governors of all states participated in a meeting to discuss Iran’s National Plan of Action for full participation of women. They participated not because they were required to do so, but because it was vital to the success of their own provincial pro- grams to work with the organization.

Afkhami suggests that the members’ concerns with social issue stood in inverse ratio to their class standing. Village and factory women were extremely open and interested, they were brave, clearly saw their issues, spoke easily, were very eager to discuss their problems and even demanded from us what they expected. They also expected us to give them a report of what we had accomplished (p. 67) In contrast, she reports, members of the upper classes were more vested in the patriarchal system and reluctant in their commitments. The profes- sional women were somewhere in between. They were open to suggestions and did what was expected of them. By the late 1970s, the WOI had over 400 branches and 120 women’s cen- ters throughout the country. Afkhami believes that the organization exercised a great deal of flexibility based on social and cultural needs of its members. “Consciousness-raising” was the most important goal of the organization, but numerous other projects were also pursued. There were day care centers in some regions, a theatre in another, and religious seminars for more conser- vative cities like Qom. “In some classes all the women were veiled. In another they could be unveiled. Elsewhere they would be half veiled and half unveiled. This flexibility made the organization very popular” (p. 74). Ayatollah Sharatmadari, the moderate religious leader, supported the organization and its activities, and his two daughters participated in the meetings of WOI. Gradually, single women, who had less freedom in terms of social interac- tion, began to attend the meetings of the association as well. The formation of the Literacy Corps by the government, a required service for both men and women, aided the WOI as young urban women were sent to teach in remote villages. Their good work and acceptance by the rural population aided the work of WOI, as these young women became a role model for the villagers (p. 88).

By 1973, it had become clear that the old discourse that “women should be educated so they could be better mothers” was no longer sufficient. With the help of Minister of Education Farrokhru Parsay, textbooks were changed to present a more egalitarian view of gender relations. Afkhami declared in a national meeting that women could not be expected to be full-time moth- ers, wives, and modern workers all at the same time and that men and women were now expected to share the duties and responsibilities in the public and the private sphere. “We are each and every one of us a complete human be- ing. We are not the other half of anyone or anything,” she announced to a stunned group of delegates, who received her bold statement with great applause (p. 95).

Soon the WOI defined its goal as fighting for the “complete equality of women in society and under the law” (pp. 95-96). A landmark legislation known as the Family Protection Law passed in 1967, and, revised in 1975, provided unprecedented rights to women. Although still far from providing complete equality, it helped the organization move closer to this goal. As a result of this law, women gained equal rights to petition for divorce and to obtain custody of their children under certain conditions. The law also lim- ited polygamy to only a second wife and stated that this was permissible un- der limited circumstances and with the permission of the first wife. By law, a man still had the right to forbid his wife from working outside the home, if he found her profession “dishonorable.” Now women obtained the same rights over their husbands’ choice of profession, at least on paper (p. 98). Laws that were based on direct text of the Quran, such as inheritance laws, could not be changed. In some instances, such as the case of polygamy, even though there is a direct reference in the Quran, advice from sympathetic senior cler- ics offered language that helped the WOI negotiate with the judiciary and the officials of the Ministry of Justice. For example, it was argued that since di- vorce is the undisputed right of a husband, and since marriage in Islam is a contract and not a sacrament as in Christianity, the husband can transfer his right to divorce to his wife at the initiation of the contract. The right to choose an abortion (with a husband’s permission, in the case of married women and by the woman’s own decision, in the case of single women) was enacted through a series of ordinance that decriminalized the procedure. But a woman’s right to travel abroad without her husband’s permission was not. There was broohaha in the media, which suggested that the WOI encouraged “women to abandon their families, to go abroad, to gamble, and to drink” (p. 104).

The first movement against honor killing in the region also began in Iran in the early 1970s, with the publication of a WOI book titled, Wife Murder in the Name of Honor: Article 179 of the Penal Code. This publication brought great public attention to the unjust law that had given a man the right to kill his wife (or sister or daughter) if he found her (or suspected her to be) in a compromising situation with an unrelated man (p. 111). After much debate and struggle, the government finally accepted to amend the law.

Day care centers were formed at most major industrial centers. The state provided the building, and the women paid for the services. A new law re- quired factory managers to give a half-hour break every three hours to nurs- ing mothers so they could feed their babies. In Tehran, factories with more than ten nursing mothers were also required to open a day care center. In ad- dition, day care centers were instituted in all government bureaus, within each building (p. 112). Similar programs were established for the provinces. The 1979 Revolution cut all of these plans short. In fact, closing day care centers became one of the first priorities of the Islamist government.

In January 1976, Afkhami was appointed Minister of State for Women’s Affairs. Iran now became the second country after France to have such a min- istry (p. 140). Since there were no models for such a ministry, women activ- ists were able to shape it in ways that would be impossible today for many of the 100 such positions across the world. Afkhami and her colleagues re- fused to acquiesce when government bureaucrats tried to ghettoize women’s issues within her portfolio. They suggested, and gained approval for, a work plan that placed the Minister of State for Women’s Affairs as coordinator of programs related to women in twelve ministries including education, labor, plan and budget, justice, health, and welfare, among others. In monthly meet- ings with senior deputy ministers from these ministries, discussions were held on the situation of women in areas under the jurisdiction of each govern- ment ministry.

Moreover, the impact of various projects on the status of women and possible ways and means of increasing women’s participation were discussed in regular meetings. This was perhaps one of the first examples of what later was called gender mainstreaming in the international community. Another important outcome of this committee was the help it provided for the pas- sage of legal provisions in support of women’s employment. These benefits included up to seven months’ paid maternity leave, half-time work with full- time benefits for mothers with children under three years of age, and child care on the work premises for all government offices and factories. Afkhami and members of the Central Council of the organization traveled to the So- viet Union, China, Iraq, Pakistan, and India, among others, to exchange views on issues related to the status of women. Relations with American feminists were more problematic. The character and priorities of the Western feminist movement of the sixties seemed unrelated to the issues and circumstances governing the lives of Iranian women. Betty Friedan and Germaine Greer were invited to Iran by the WOI. Friedan also interviewed the Shah and Queen Farah and wrote a positive account of her trip to Iran for Good House- keeping. But here again differences crept in. The Americans were concerned with human rights violations in Iran, and the Iranians often found the attitude of the American feminists condescending. Germaine Greer was chal- lenged by students at Pahlavi University and accused of a colonialist attitude of superiority toward Iranian women, proving once again that certain types of Western activism do not travel well in the Middle East. As a result, little was accomplished by this exchange.

By the late 1970s, Iran was seen as a world leader in the campaign for international women’s rights, despite the country’s authoritarian government. Lack of democracy was of course not limited to Iran but pervasive in the Middle East from Egypt and Syria to Iraq, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, and Yemen, and, in contrast, rights that Iranian women had gained were unprecedented in the region. Iran was a relatively prosperous third World country, a predominantly Muslim nation that supported women’s advancement. It had good relations with non-aligned nations and served as an important pole of attraction between the Eastern and Western blocs (p. 132). At the preparatory meet- ing for the First UN World Conference on Women in Mexico City in 1975, sixteen representatives from all regions of the world approved the draft Plan of Action, which was prepared by the Iranian delegation and subsequently submitted to the general assembly. A modified version of the Plan was ratified at a national meeting of the WOI in Tehran, where 10,000 delegates participated. The next UN conference on women was scheduled for Tehran in 1980 but had to be moved to Copenhagen because of the revolution.

Looking back on her experience in Iran, Afkhami regrets the fact that in pursuit their goals, she encouraged the WOI leadership to join the single party Rastakhiz (Awakening Party), which the Shah formed in 1975 and then asked all his loyal citizens to join. Afkhami sees this as her major political mistake. She insists that she never wrote a direct report for the Shah, nor had direct orders from the Shah. This may very well have been the case, but in a nation where the dreaded SAVAK secret police infiltrated all institutions from trade unions to student groups and the state closely monitored even the slightest political activity, WOI was seen as a direct arm of the regime. For this, as well as its dramatic challenge to traditional gender roles, the organi- zation was highly resented by the opposition, both on the right and on the left.

Afkhami’s amazing record of achievements at the helm of WOI, as well as her candor in acknowledging the organization’s political mistakes, is what makes this book a must read for all who are interested in gender reforms in the Middle East. The book is not devoid of humor despite the serious na- ture of its topic and neither is Afkhami in her lecture tours. In a recent talk about the book, in which this reader was present, she brought the floor down when she likened her story to the well-known joke in which the doctor emerges from the operating room and says, “The operation was extremely successful, unfortunately the patient died!”

What astonished this reader was to learn about the level of suspicion toward declarations of government, not just among the general public but among many political leaders, including the Minister of Women’s Affairs. It seems that Afkhami was never briefed on the character of the brewing op- position or the close alliance between the Islamist clerics and the student movement. In the late 1970s, when a group of Islamist students at Tehran University demanded a segregated cafeteria and buses through a series of pro- tests, Afkhami (like many average Iranian citizens) assumed that these pro- tests were a provocation orchestrated by the secret service in an attempt to discredit the Islamists. Obviously, this was also because Afkhami, who was part of a small western-educated elite, simply could not believe that young college students would be so conservative (p. 188). Instead, like many other Iranian citizens who had learned to doubt reports in the government con- trolled media, she assumed that the whole thing was fabricated by the SAVAK secret police. As a result, she decided not to plan a counter demonstration. Even when the Shah brought up the subject in a meeting and showed his annoyance by this lack of response, Afkhami continued to believe that the whole thing had been concocted by the SAVAK and writes that at the time “we did not wish to entangle the organization with what seemed to be a fabricated issue, hence we did not encourage [a counter demonstration] ” (p. 189).

Likewise, when Muhammad Reza Shah criticized the “Marxist-Islamist” alliance and warned of this danger, Afkhami felt:

[That the whole concept of] Marxist-Islamists was a product of the machi- nation of the secret police to confuse the rest of society. It was so strange for us to think that some would want to combine Marxism with Islam. We did not believe such groups could exist. No one I spoke to thought a university-educated intellectual could be so fanatical. We thought the cler- ics, the mullahs, in some distant village would have such prejudiced views but not people on college campus, not any intellectuals. No one believed such a thing! (p. 189-190)In 1978 Afkhami was in New York working with the office of the UN Secretary General to finalize the agreement between Iran and the UN to set up the International Center for Training and Research on Women (INSTRAW), which was to be established in Tehran. A late-night phone call from her husband gave her a veiled message from Queen Farah that she should not return. This message saved Afkhami from the fate that befell her mentors and peers, Premier Amir Abbas Hoveyda and Minister Farrokhru Parsa, both of whom were executed when the Islamists took over.

The WOI did play a role in the 1979 revolution, though not the one its secular feminist leaders had expected. Many of the recruits joined the Islamist demonstrations ons and lent their support to Ayatollah Khomeini. She recalls that in one of the early demonstrations in the province of Kerman a group of veiled women joined the protests against the Pahlavi regime. When Afkhami inquired about the political affiliations of the women, she was told by an executive secretary of WOI, “They are our own members. We kept saying we should mobilize them, we should mobilize them. We didn’t say we should mobilize them for what. Now that they are mobilized they say death to the shah!” (p. 214) But many devoted members of the WOI also participated in the historic March 1979 women’s demonstrations after Khomeini abolished the Family Protection Law and then attempted to reimpose the veil, as one of the first measures of the new regime.

Throughout the interview, Afkhami argues that her organization had a great deal of autonomy from the court and laments the fact that it was so identified with the royal family. She insists that the Shah, especially his sister and his wife, simply aided the organization rather than initiate reform and did so if the organization’s projects did not overtly flout religious laws and practices. Afkhami argues that Princess Ashraf was mostly involved in inter- national affairs such as the UN, while the Shah was interested in moderniz- ing the nation. So long as the WOI worked toward defined common goals, it was left to its own devices. In hindsight, Afkhami laments the close identifi- cation of her activities and those of other women in the organization with the royal court. She admits that in the highly conservative milieu of Iranian society it was easier to reform women’s status by attributing all new ideas and programs of the WOI to the Shah and hi

If we said Princess Ashraf or his majesty were interested in a project, or had certain views about it, many barriers before us were lifted, or perhaps we thought they were lifted. After a while we used the same strategy to prevent possible backstabbing. I think this was a big mistake that turned many groups, especially the intellectuals who opposed the Shah, against our organization… neither [Princess Ashraf] nor the Queen, nor the shah, nor the Prime Minister nor anyone else, in all t of the WOI interfered in our affairs, gave us suggest quested or ordered anything. We were the ones who hand” methods to stop the opposition of the tradition reaucrats as much as possible. Unfortunately more tha ter the revolution I still have to answer for our own no relationship to the reality of our situation (p 217-218).

Afkhami’s dilemma remains that of Middle East. Do they affiliate themselves with an authoritarian government that is nevertheless interested in pushing for gender reforms, or do they back an opposi- tion that speaks for restoration of human rights and an end to Western intervention but is willing to ally itself with anti-feminist Islamist tendencies, and hence is sure to further push back women’s rights upon assumption of power?

NOTE

1. This organization helps create culture-specific training curricula on leader- ship, capacity building, and the use of technology for advocacy in Muslim majority countries. WLP works with major grassroots women’s organizations in fifteen coun- tries in Asia, Africa, and the Middle East. The partnership has been instrumental in creating a space for north-south dialogue and building support for women in the glo- bal south, especially the MENA reg

Book Endorsement & Praise

“A moving narrative that competes with some classics of Middle East women’s studies” — Janet Afary, Journal of Middle East Women’s Studies