Overview

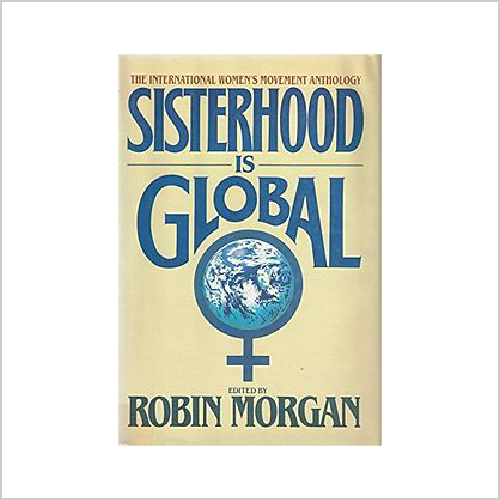

Sisterhood is Global: The International Women’s Movement Anthology – November 1, 1996

Sisterhood Is Global has been revered as the essential feminist text on the international women’s movement since its first appearance, when it was hailed as “a historic publishing event.” The anthology features original essays Morgan commissioned from a deliberately eclectic mix of women both famous and less known-grass-roots activisits, politicians, scholars, querillas, novelists, social scientists, and journalists-representing seventy countries, from every region and political system, with particular emphasis on the Global South. These truth-telling, impassioned essays celebrate the diversity as well as the similarity of women’s experience; they also reveal shared female rage, vision, and pragmatic strategies for worldwide feminist solidarity and political transformation.

The first such international collection, Sisterhood Is Global became an instant classic and remains unequalled in its breadth and comprehensiveness. The book covers Afghanistan to Zimbabwe, and includes moving essays from such distinguished writers as Marjorie Agosin (Chile), Ama Ata Aidoo (Ghana), Shulamit Aloni (Israel), Peggy Antrobus (Caribbean), Simone de Beauvoir (France), Lidia Falcon (Spain), Hema Goonatilake (Sri Lanka), Fatima Mernessi (Morocco), Nawal El Saadawi (Egypt), Ana Titkow (Poland), Marilyn Waring (New Zealand), and Xiao Lu (China).

Book Excerpt

Iran: A Future In The Past–The “Pre-revolutionary” Women’s Movement

By Mahnaz Afkhami In Sisterhood Is Global: The International Women’s Movement Anthology / Robin Morgan (ed.) / New York / 1984

In December of 1979, Ms. Farrokhrou Parsa, the first woman to serve in the Iranian cabinet, was executed after a trial by hooded judges-a trial at which no defense attorney was permitted, no appeal possible, and the defendant had been officially declared guilty before the proceedings began. She was charged with “expansion of prostitution, corruption on earth, and warring against God.” Aware of the hopelessness of her case, she delivered a reasoned, courageous defense of her career decisions, among them a directive to free female schoolchildren from having to be veiled and the establishment of a commission for revising textbooks to present a nonsexist image of women. A few hours after sentence was pronounced she was wrapped in a dark sack and machine-gunned.

Ms. Parsa, whose mother had been exiled for her stance on women’s rights (especially her opposition to the veil), had been educated as a medical doctor but chose to serve as a teacher and, later, as principal of a girls’ high school. In 1964 she was one of the first six women elected to Parliament. In 1968 she was appointed Minister of Education. At the time of her death she had been retired for four years.

She was not a heroic figure but a hard-working, disciplined woman who struggled to achieve her position in government. She was a practical, level-headed feminist. The significance of her position for the Iranian women’s movement rested not so much in her considerable personal achievements but in that she was one of hundreds of thousands. Those who executed her also understood this and staged the event as a symbolic attempt to reduce her-and through her the type of woman she represented-to an insignificant, lifeless shape in a dark sack. In the year following her death, many women marched against the tyranny of the mullahs. Many were beaten, stabbed, imprisoned. Some of the very young were tried and executed without ever identifying themselves as other than “fighters, daughters of Iran.” No further identification was necessary. It was a type of woman the regime meant to destroy.

History has shown that execution of people who are committed to an idea seldom destroys the idea. At this moment the regime of the mullahs shows signs of crumbling. Whatever form of government replaces it must come to terms with feminism in Iran. The struggle of Iranian women during and after the “revolution,” and their presence in all social and political movements, means that what they have gained in terms of awareness, organizational experience, and political consciousness must be taken into account. The future must begin at the point when persecution drove the feminist movement underground. It is with this belief that, although I must discuss the Iranian women’s movement in the past tense, I speak of it not as a thing of the past, but as a strong foundation for the enormous work lying ahead.

The single most important factor to keep in mind about the movement is that its most spectacular achievements took place within a time span of less than two decades. As late as 1962, Iranian law regarded women as being in the same class as minors, criminals, and the insane. They Could not vote or stand for public office, were not allowed the guardianship of their own children, could not work or marry without permission of their male “benefactors,” could be divorced at any moment (with or without their prior knowledge, through the utterance of a simple sentence by the husband), and could be faced with the presence of a second, third, or fourth wife in their home at any moment-with no legal, financial, or emotional recourse.

At the beginning of the 1960’s, feminists had two points of strength. One was the existence of a national leadership which, although by no means feminist in orientation, at least was committed to modernization and change. But the second and greatest strength was the existence of an increasing number of educated women with an already respectable history of feminist endeavors-beginning with the establishment of the Patriotic Women’s League and the publication of its organ Nesvane Vatankhah in 1923, leading in turn to the creation of organizations throughout the country, and culminating in the establishment of a federation of fifteen organizations called the High Council of Women’s Organizations of Iran, which concentrated its efforts on the achievement of women’s suffrage. The national referendum of 1963 reflected general support for the six-point reform program, which included land reform and the franchise for women.

The first serious victory brought about a wave of reaction from the fanatic religious opposition. Riots were organized under the leadership of the (then scarcely known) Ayatollah Khomeini, whose earlier petition to the Shah against land reform and women’s franchise had been ignored. Marching mobs demonstrated against the new role of women. The Ayatollah’s activities were temporarily curtailed when he was exiled to Turkey. Feminists, however, became even more conscious of the extent of opposition to their ideas and of the need for unification of their own forces. In 1964, fifty-one women representing diverse groups and interests came together to study various ways of achieving a more viable organizational structure for women’s activities. In 1966 the draft constitution of the Women’s Organization of Iran (WOI) was presented to an assembly of representatives from across the nation. The constitution of the new organization envisaged a grass-roots, nationwide movement whose officers would be elected from among the members in each branch. These officers would in turn elect an eleven-member central council which would provide guidelines and set goals. Princess Ashraf, the twin sister of the Shah and by far the most powerful woman in the country, was asked to act as honorary president; her patronage was to assure the organization political leverage in the battle against its fanatic enemies. The organization’s initial efforts were based on a few simple, agreed-upon concepts: that every individual in society must be encouraged to learn, work, grow, and contribute to nation-building; that this goal could be achieved within the spirit of Islam and the cultural traditions of the nation; that full participation of women must be achieved by women themselves through methods which they choose; that education in the broadest sense is the most important vehicle to bring about change; that economic independence is one of the first priorities and the basis for achievement of other rights; and that the acquisition of power, through the infiltration of feminists in various institutions and mobilization of groups from various strata of society, is a prerequisite for gaining the means to achieve these goals.

Feminism was thought to be a Western phenomenon. But an idea’s origins, it was agreed, ought not to be the main consideration in one’s judgment of its validity; Christianity came from the Middle East while democracy was of Western origin. One need not reinvent the wheel to satisfy one’s chauvinism. Yet the organization stressed the importance of reinterpreting each concept within the cultural framework of the Iranian people. The movement’s immediate audience was the growing urban, educated, middle class, but ways had to be found to reach the rural and urban masses, and communication had to be devised in terms relevant to their lives. As one literacy-corps woman pointed out, It was fruitless to discuss the finer points of human rights with a pregnant, illiterate, village woman who was doing her chores as she breast-fed one baby, tried to extricate her skirts from the clutches of another child, and kept a worried eye on her two other children fighting and screaming nearby. The ideas were not only alien to her life, but worse, they were irrelevant.”

It was imperative for the movement to gain access to decision-making at the national level in order to redirect the entire developmental process to include women. It was crucial to create awareness that women are the most significant element in the solution of these problems. Thus, the movement was faced with the tasks of gaining support among the decision-makers on the one hand, and mobilizing mass support among women on the other.

Mass mobilization had to begin pragmatically, by offering useful services in order to gain trust and support. Accordingly, a main category of functions included the provision of vocational training and literacy classes, childcare, legal and professional counseling, family planning, and a wide range of cultural and sport activities for the young (depending on the expressed preference, talent, and know-how of each group in each area; recitation of the Koran, for example, would be chosen by women in one area and organization of a soccer team or a self-defense class in another).

In order to mobilize support among the decision-makers, however, goals of the movement had to be disguised in terms palatable to power groups who were not feminist but who might be persuaded to back ideas in tune with some of their own goals. Thus, special programs to combat illiteracy among rural women were not demanded solely on the basis of women’s right to education, but as a necessary means of modernization. Special vocational training for women was sought not only on the grounds of their rightful access to better-paying jobs, but for the sake of eliminating sociocultural problems inherent in large-scale importation of foreign labor.

Legal action usually followed years of discussion within the movement in order to transform vague feelings of injustice into coherent and well-reasoned demands for change. Thorough research was carried out in terms of the socioeconomic background of each proposal, as well as the cultural and religious factors to which the proposal would relate. Then there followed publication of works on various levels of complexity for women with different levels of education.

Each legislative proposal was brought to the attention of the more enlightened senior religious authorities, and their views were incorporated into the body of the laws. Often they provided valuable advice on ways of preparing legislative texts which would embody feminist ideas in language which avoided conflict with religious dictates, especially the text of the Koran. Their approval, however, did not bring immunity from attack by the more fanatic leaders, who were fully aware that the rapidly changing status of women presented a threat to their world view, power, and prestige. (The Family Protection Law, for example, not only presented a view of women which approached the concept of equality within the family but brought family disputes within the realm of secular law and thus outside clerical jurisdiction.)

The proposals would then be subject for discussion at a high-level committee of the women’s organization to which senators, judges, and various other high officials would be invited as participants. Endless hours of decorous discussions on the sacred role of motherhood and the “special but decidedly different” intellectual and emotional make- up of women would be patiently tolerated. Diplomatic presentation by some feminists would be juxtaposed against more radical statements by other feminists. Slowly the discussions began to have an effect, producing surprising changes among the male participants. What finally emerged was often couched in terms which were not our ideal (customary introductory slogans regarding respect for religion and the sanctity of the family became a necessary part of each document). But the sacrifices were considered well worth the results.

One phase of legal action always involved convincing the Monarch-whose national role was the essence and symbol of patriarchy. Since he was regularly briefed by the Queen and Princess Ashraf (both intelligent, active, professional women), constantly exposed to international opinion and attitudes, and possessed by a vision of Iran as a “progressive” nation, it would sometimes suffice to demonstrate to him the importance of the proposal to national development. On issues which were in apparent conflict with the text of the Koran. he took a very rigid stance. On the eve of a legal seminar, the Minister of Court informed me of His Majesty’s concern over our proposed stance on inheritance laws. This was both a personal concern and an indication of mounting pressure from the fundamentalists. One long legal campaign had produced the 1975 far-from-ideal but still significant revision of the Family Protection Law. We had supported the compromise as a step forward, but as soon as the law passed we began to prepare the next revision proposals. It was hopeless at the time of the 1975 revision to try to achieve equal powers for partners within the family during the husband’s lifetime. But we managed to secure the right of women to legal guardianship of their children after the death of the father. (In the majority of Islamic countries guardianship of children after the father’s death is given to the male members of the father’s family.) In the same law, although we were not able to strike out the right of the husband to prevent his wife from engaging in a profession “repugnant to his family honor,” we were able to include the same prerogative for the wife. Practically speaking, neither provision is enforceable, but the revision is significant: for the first time women were legally considered to possess “honor” in their own right.

The Passport Law and Article 179 of the Penal Code were cases where negative publicity and great controversy forced us to put aside our proposals for a time. The Passport Law required a woman to present the written permission of her husband in order to be issued a passport to travel. Senator Manouchehrian, president of the Women Lawyers’ Association, made a speech arguing for freedom of travel, basing her argument on the Koranic dictum that no one has the right to detain another from pilgrimage to Mecca. An avalanche of attacks ensued and we were portrayed as advocates of “travel by honest Moslem womenfolk to the West to shop and gamble.” Ms. Manouchehrian’s next speech was curtly interrupted by the President of the Senate, who publicly accused her of misrepresenting Islam. The publication of a pamphlet called “Legalized Wife-killing” by the WOI also brought a backlash. Article 179 of the Penal Code states, “If a man witnesses his wife in the act of intercourse or a situation which could be construed as being engaged in intercourse with a man other than her husband and injures or murders one or both of them, he is immune from punishment.” The cases which occurred with frequency involved murder of the woman, seldom the other man, and were rarely the result of a spontaneous reaction. As late as 1974 an absurdly broad interpretation by a fanatic judge had extended this immunity to a brother who had murdered his sister because he had seen her get out of a taxi accompanied by a stranger. The opposition to our pamphlet, however, began with a wave of propaganda implying that feminists supported adultery and wished to “expand prostitution.” We were forced into tactical retreat on this issue also. It was extremely difficult to fight implications of sexual immorality on the relatively sophisticated grounds of the human rights of women. It took us five years of quiet negotiation and a low-key but extensive media campaign to be able to relaunch the effort to change these laws.

There were times when we were successful in implementing legal change without arousing much public attention. Such was the case of abortion, which was made legal by removing the penalty for performing the operation embodied in a law dealing with medical malpractice. Ministry of Health officials agreed to cooperate, mostly because of the added impetus for the unsuccessful birth-control campaign. It was agreed that to minimize organized attacks by the opposition, publicity would be avoided, so legalization was announced through internal memos of the Ministry of Health, Ministry of Justice, and the WOI. We were fully aware of the limited impact of the law under these circumstances, but we agreed because even under these conditions the law would save tens of thousands of women from disability or death.

Legal changes were only the beginning; implementation was even more complicated and difficult. Important as it was to gain the right to sue for divorce, it would be useless to a woman who had no means of financial support. Raising the legal age of marriage was of limited value since in some outlying villages, records of birth were scribbled on the front page of the Koran and one child’s birth date could be given as another’s. The problem of implementation was related to the general problems of education and socioeconomic development-which brought us back to our primary goal: full integration of women in the process of development. Nevertheless, legal change is of tremendous value. As a reflection of what a society thinks about the role of women, the laws affect a woman’s self-appraisal as well as the attitude of men.

In every area of women’s-movement activity, we faced potential or actual opposition from fundamentalist religious figures who enjoyed influence among the people, had access to the masses through the network of mosques, and used established religious events as occasions to affect public opinion. Their claim to monopoly on the interpretation of the sacred texts, their presumed communion with God, prophets, and Imams, and their mastery of the vehicle of oral communication were strong means of reaching the illiterate masses. However, the fundamentalists would have had little impact among the urban intelligentsia and middle classes were it not for the vital assistance they received from the radical Left.

The Left saw class struggle as the only legitimate one and viewed any “revisionist” attempt to bring about progress within the system as detrimental to the success of revolution: once the class struggle was won and the proletariat achieved victory, then the problem of women (a by-product of the class system, of course), would automatically disappear. Accordingly, the growing influence of the women’s organization among the people was seen as a threat to be counteracted. The radical Left, however, enjoyed very little mass support, owing to the antireligious stance of Marxism as well as a deep-rooted fear of the Soviet Union’s threatening presence along the 1200 miles of shared border with Iran. So, learning from past mistakes, the Left shrewdly chose to join forces with the religious fundamentalists, bringing political know-how to the latter’s activities. Indeed, considerable sophistication (as well as a lack of political scruples) was necessary to be able to choose the feminist repugnance to the objectification of women as a battle cry for a movement whose entire philosophy was based on the negation of women’s social existence. Thus, Leftist university women suddenly put aside their jeans to don black chadors. They sometimes zealously exceeded the mullahs’ mandate by wearing gloves to cover their hands. The controversial issue of abortion, which had been handled with such extreme caution, suddenly became the subject of front-page headlines one year after actual legalization and on the day of the first fundamentalist demonstrations. In the hysterical media “campaign just before and after the revolution, feminists who could see beyond particular political posturings could recognize the antifeminist techniques: allegations of immorality, of weakening family ties, and of sexual misconduct were spread through the media, fanned by revolutionary zeal and with astounding power and success. Pictures of women in bathing suits were used to support charges of prostitution against women working in the government bureaucracy. No holds were barred in the smear campaign to belittle and discredit women leaders. Khomeini repeatedly called any unveiled woman “naked,” and any woman who had normal professional contact with men “a prostitute.”

Yet despite the power of the opposition, by 1978–only twelve years after its establishment-the Women’s Organization of Iran had grown into a network of 400 branches and 118 centers, with 51 affiliated organizations, including religious minorities, professional associations, and other special-interest groups. I And we had accomplished the following:

- During the first half of the 1970’s the number of girls attending elementary school rose from 80,020 to 1,508,387; the number of girls attending vocational training schools rose tenfold; the number of women candidates for the universities rose seven times. By 1978, 33 percent of all university students were women and they began to choose fields other than traditionally female occupations. Further encouragement was provided through a quota system which gave preferential treatment to eligible girls who volunteered to enter technical schools. In 1978, the number of women who took the entrance examination for the School of Medicine was higher than that of men.

- Three years of research, experimental teaching, and discussion by an ad hoc committee of members ofWOI and the faculties of Tehran and National Universities established an accredited program of women’s studies at these universities.

- In employment, priority was given to training women for semiskilled and skilled work. All laws and regulations were revised to eliminate sex discrimination, and equal pay for equal work was incorporated into the body of all government rules. All regulations regarding housing, loans, and other job benefits were adjusted to eliminate discrimination.2

- In 1979 there were 2 million Iranian women in the labor force and 187,928 enrolled in academic and specialized fields; 146,604 worked as civil servants, and of these 1666 were managers or directors. There were 1803 women university professors. Women worked in the army, in the police force, as judges, pilots, engineers-in every field except religious activities. Schools of theology were the only academic institutions closed to women.

- Women were encouraged to run for political office. In 1978 a vigorous mobilization campaign resulted in the election of 333 of 1660 candidates to local councils. Twenty-two women were elected to Parliament and two served in the Senate. There were one cabinet minister, three sub-cabinet under-secretaries (including the second highest position in the Ministries of Labour and Mines and Industries), one governor, an ambassador, and five mayors.)3

- Perhaps the most important accomplishment was the formulation of the National Plan of Action-based on the results of more than 700 seminars, informal gatherings, and conferences throughout Iran. It was presented to the cabinet and approved in May 1978. This event was significant not only because of the enormous task of achieving consensus among women on all major issues, but also because cabinet approval included approval of the machinery for implementation, through the designation of a special committee in each of twelve ministries to plan, implement, and monitor efforts toward full integration of women in society.

- The movement considered international action on feminist issues one of the most important means of achieving its goals. Exchange of information, pooling of research resources, and mutual assistance between women’s groups in different nations (especially in times of political and social tension) is vital in terms of both pressuring governments and bringing crucial moral support. The WOI was successful in channeling substantial financial aid to UN programs for International Women’s Year. The Iranian delegation introduced the idea and the funds for the creation of the Regional Center for Research and Development for Asia and the Pacific, and for the International Center for Research on Women. The beginning of the 1980’s was to have been the birth of a new phase in the history of Iranian women and a significant era for women of all Third World Moslem nations.

Within a few months, the entire picture changed. The convulsions within the nation turned to upheaval and finally revolution. In February 1979, Khomeini returned to Iran. Within a few months, a systematic and vigorous attempt began to reverse all the changes we had achieved. Women were eliminated from all decision-making positions within the government. Those who remained at low levels were required to wear the veil. The President (considered moderate as compared to other leaders), stated, “It is an obligation of the female to cover her head because women’s hair exudes vibrations which arouse, mislead, and corrupt men.” The Family Protection Law was set aside. Childcare centers were closed. Abortion became illegal under all circumstances. Women were ruled unfit to serve as judges. Adultery became punishable by stoning. The Women’s Organization was declared a den of corruption and its goals conducive to the expansion of prostitution. University women were segregated in cafeterias and on buses. Women who demonstrated against these oppressive rules were slandered, accused of immoral behavior, attacked, and imprisoned. Opposition grew. Executions became a daily occurrence.

But the regime held within its reactionary philosophy and oppressive style the seeds of its own destruction. Disillusioned with the incompetence and inhumanity of the mullahs, the Iranian people (both inside the country and in the West, where millions have fled to escape the tyrannical theocracy) have organized themselves to overthrow the regime and install a government respectful of Iranian national and cultural traditions as well as those of law and reason.

Women have had an active role in every opposition political group. We have learned a lesson, though: we know now that whatever one’s political preference, the main battle for women always remains in the arena of sexual politics. The years ahead will be difficult. To unite a torn and battered nation and rebuild what had been destroyed is a monumental task. But as I contemplate the future of Iran, a reassuring image gives me hope. I recall a young woman I met in the southern village of Zovieh. She had finished her military service in the literacy corps to return to her home and establish a school in which she taught all subjects to all four grades. On the day I saw her, she was walking out of a village meeting in her faded uniform, flushed and proud, followed by the old men who had just selected her Kadkhoda, or “elderman,” of the village.

Those who have struggled and those who have died sacrificed so that women like her may exist.

She is the future.

Notes

1. The centers provided vocational training, literacy classes, childcare, legal and professional counseling, and family planning through a professional staff of two thousand and a volunteer staff of seventy thousand to approximately a million women each year. The WOI School of Social Work selected potential staff members from among village women and trained them for two years to return and work in their own environment. 2. A legislative package supportive of women’s employment was prepared and approved by Parliament. It contained provisions for a working mother to work half time, up to her child’s third year of age. The three years would be considered equivalent to fulltime work in terms of seniority and retirement benefits. It also provided for up to seven months maternity leave with full pay. Most important, it contained a provision which made the establishment of childcare facilities on the premises of factories and offices obligatory. These centers were supervised by an elected committee of the mothers who were allowed paid time off to perform this function. 3. The degree of political awareness reached by the masses of Iranian women became strikingly apparent during the antigovernment marches of 1978-79. In a meeting of the secretaries of WOI we asked the Secretary of Kerman Province about the veiled women who had taken part in a recent demonstration. “Who were they?” we asked. “Our own members,” she said. “You kept saying ‘Mobilize them.’ Now they are mobilized, and they shout ‘Long Live Khomeini.’ ” Yet to this day we are all still in agreement that what is important is that they marched and shouted their will. That it was in support of a destructive force came from political naivete which only time and experience can correct.

Suggested Further Reading

Azari, Farah. Women of Iran. London: Ithaca Press, 1983. Bamdad, Badr al-Muluk. From Darkness into Light: Women’s Emancipation in Iran.Trans. F. R. C. Bagley. Hicksville, NY: Exposition Press, 1977. Farman-Farmaian, Sattareh. “Women and Decision-Making: With Special Reference to Iran and other Developing Countries.” Labour and Society, Geneva, Apr. 1976. Henderson, Behjat. “The Effect of Modernization on the Roles of Iranian Women.” Occasional Papers in Anthropology, Buffalo, 1979. Nashat, Guitty, ed. Women and Revolution in Iran. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1983. Population and Family Planning in Iran. United Nations Mission Report. New York: United Nations, 1971. Rachlin, Nahid. Foreigner, A Novel of an Iranian Woman Caught Between Two Cultures. New York: W. W. Norton, 1978. Tabari, Azar, et al, eds. In the Shadow of Islam: The Women’s Movement in Iran. London: Zed Press, 1982. (Among the publications of the Women’s Organization of Iran are a series of Comparative Studies on the Laws of Iran and international conventions and declarations on the role of women. These are in Persian. The only copies in existence after the revolution are, I believe, those I have donated to the library of the Foundation for Iranian Studies in Washington. They will photocopy and at times translate segments for the use of serious scholars. Publications of the Women’s Organization of Iran’s Research Center available in English are the following.-M.A.) Afkhami, Mahnaz. The National Plan of Action for the Improvement of the Status of Women in Iran: Ideology, Structure, and Implementation. This was to have been published by Ziba Press, Tehran, 1979. Moser-Khalili, Moira. Urban Design and Women’s Lives. Tehran: Women’s Organization of Iran, 1976. Iranian Women, Past, Present and Future. Tehran: Women’s Organization of Iran, 1976. Sources in Persian: Karnameye Sazemaneh Zanane Iran. Tehran: Ziba Press, 1978. Naqshe Zan Dar Farhang va Tamadone Iran. Tehran: Bisto Panje Shahrivar Press, 1971.

Mahnaz Afkhami was born in Kerman, Iran, in 1941. She taught at the National University of Iran and in 1968 became chair of the English department. She is the founder of the Association of Iranian University Women and served as the secretary general of the Women’s Organization of Iran from 1970 until the revolution of 1979. She was Minister of State for Women’s Affairs from 1976 to 1978, when the position was eliminated on the eve of the religious upheaval. She has written and lectured extensively on the women’s movement and headed the Iranian delegation to the conferences of the International Council of Women in 1972 (in Lima) and again in 1973 (in Vienna). She headed the Iranian delegation on visits to the USSR (1974) and the People’s Republic of China (1974), on the invitation of the women’s organizations of those nations. She also headed the Iranian delegation to the UN Consultative Committee for the World Conference of the International Women’s Year in New York (1975), and the Iranian delegation to the Commission on the Status of Women’s 1978 session. She served as a member of the High Council of Family Planning and Welfare, the board of trustees of Kerman University, and the board of trustees of Farah University for Women. Among her writings are Notes on the Curriculum and Materials for the Women’s Studies Program for Iranian University Women. She is presently the executive director of the Foundation for Iranian Studies in the US and is preparing a History of the Iranian Women’s Movement in the Twentieth Century. She is married and has a son, Babak.

Book Endorsement & Praise

“The Whole Feminist Catalogue: A fascinating compendium.” ―New York Times Book Review

“[A] vast amount of cultural and factual information . . . a powerful contribution to the literature of women’s studies and human rights.” ―Booklist

“One of the most important human documents of the century.” ―Alice Walker, author of The Color Purple

“No reader, classroom, or library concerned with women or international politics can afford to be without it.” ―Gloria Steinem, author of My Life on the Road