Overview

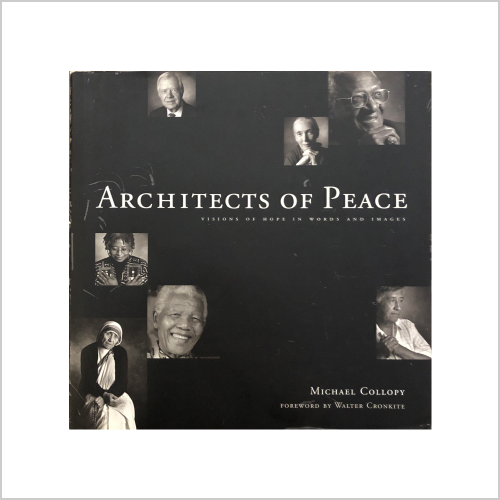

Architects of Peace: Visions of Hope in Words and Images/ Michael Collopy

Publisher: New World Library (August 20, 2002)

Seventy-five of the world’s greatest peacemakers — spiritual leaders, politicians, scientists, artists, and activists — testify to humanity’s diversity and its potential. Featuring 16 Nobel Peace Prize laureates and such visionaries as Nelson Mandela, Cesar Chavez, Mother Teresa, Dr. C. Everett Koop, Thich Nhat Hanh, Elie Wiesel, Archbishop Desmond Tutu, Coretta Scott King, Robert Redford, and more, the book profiles figures often working at the very nucleus of bitter conflicts. 100 black-and-white photos are included.

Book Excerpt

By Mahnaz Afkhami In Architects of Peace: Visions of Hope in Words and Images / Michael Collopy and Jason Gardener (eds.) / New World Library / October 2000 Translation in Persian

The century just passed was marked by unprecedented violence and cruelty. Most nations suffered or contributed to war, destruction and genocide, the most egregious of which–the two world wars and the holocaust–began and occurred mainly in the west. Untold numbers were sacrificed at the altar of ideology, religion, or ethnicity. Innocent people were led in droves to their destruction in various forms of gulags–prisons large enough to pass for cities and cities confined enough to pass for prisons. Women and children everywhere suffered most from violence not of their making perpetrated against them in national wars, in ethnic animosities, in petty neighborhood fights, and at home. Many of us have lived most of our lives under the threat of total annihilation because mankind achieved the technological know-how to self-destruct. The end of the Cold War removed the immediate causes of wholesale destruction–but not the threat that is contained in our knowledge. We must tame this knowledge with the ideals of justice, caring, and compassion summoned from our common human spiritual and moral heritage, if we are to live in peace and serenity in the 21st century.

The promotion of a culture of peace requires more than an absence of war. In the past 200 years most of the world lived directly or indirectly within a colonial system. This system reflected an increasingly divided world of haves and have-nots. The modernizing elite in the technologically and economically poor nations responded to colonialism by seizing the power of the state and using it to change their societies, hoping to achieve justice at home and economic and cultural parity abroad. The politics of changing traditional social structures and processes by using state power did not always result in social progress and economic development, but it did lead to state supremacy and autocracy. In the more extreme cases autocratic regimes were transformed to a variety of forward looking or reactionary totalitarianism–of socialist-Marxist, fascist, or religious-fundamentalist types. These systems clearly failed or are failing. But at the time they were adopted, to many they represented hope and a promise of economic change, distributive justice, and a better future. As we move forward in the first decades of the new millennium, economic and political globalization is likely to weaken the state. Deprived of the protection of the state, a majority of the people in the developing countries will have to fend for themselves against overwhelming global forces they cannot control. The most vulnerable groups, among them women and children, will suffer most. Clearly, any definition of a culture of peace must address the problem of achieving justice for communities and individuals who do not have the means to compete or cope without structured assistance and compassionate help.

As we move into the 21st century, women’s status in society will become the standard by which to measure our progress toward civility and peace. The connection between women’s human rights, gender equality, socioeconomic development, and peace is increasingly apparent. International political and economic organizations invariably state in their official publications that achieving sustainable development in the global south, or in less developed areas within the industrialized countries, is unlikely in the absence of women’s participation. Women’s participation is essential for the development of civil society, which, in turn, encourages peaceful relationships within and between societies. In other words, women, who are a majority of the peoples of the earth, are indispensable to the accumulation of the kind of social capital that is conducive to development, peace, justice, and civility. However, unless women are empowered to participate in the decision-making processes; that is, unless women gain political power, it is unlikely that they will influence the economy and society toward more equitable and peaceful foundations.

Women’s empowerment is intertwined with respect for human rights. But we face a dilemma. In the future, human rights will be increasingly a universal criterion for designing ethical systems. On the other hand, the “enlightened” optimism that spearheaded much of the humanism of the 19th and 20th centuries is now yielding to a pessimistic view that we are losing control over our lives. We sense a growing cynicism engulfing our view of government and political authority. In the west, where modern technology is invented and domiciled, many people feel overwhelmed by the speed with which things moral and material around them change. In non western societies, the inability to hold on to some constancy that in the past yielded a cultural anchor and therefore a bearing on one’s moral and physical position today often leads to normlessness and bewilderment. In the west or east, no one wishes to become a vessel for a technology that evolves uncontrolled by human will. On the other hand, it is becoming increasingly difficult for any one individual, institution, or government to exert its will meaningfully, that is, ethically, to mold technology to human moral needs.

The seemingly uncontrollable technology, however, will be a harbinger of great promise if we agree on a set of shared values contained in our major international documents of rights, and if we adopt a method of deciding that reflects our common values justly. After all, we have gained almost magical powers in science and technology. We have overcome the handicaps of time and space on our planet. We have uncovered many secrets of our universe. We can feed and clothe the peoples of our world, protect and educate our children, and provide security and hope for the poor. We can cure many of the diseases of body and mind that were deemed scourges of humanity only a few decades ago. We seem to have passed the era of the absolutes where leaders assumed the right to incarcerate, slaughter, or otherwise constrain their own people and others in the name of some imagined good. We have the ability to achieve, if we master the needed goodwill, a common global society blessed with a shared culture of peace that is nourished by the ethnic, national, and local diversities that enrich our lives. To achieve this blessing, however, we must assess our present situation realistically, assign moral and practical responsibility to individuals, communities, and countries commensurate with their objective ability and, most importantly, we must subordinate power in all its manifestations to our shared humane values.