Overview

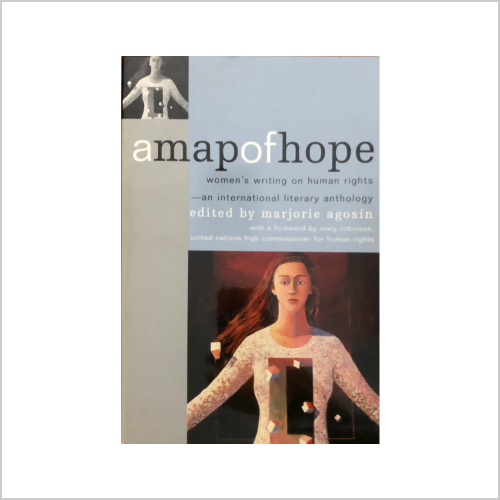

A Map of Hope: Women’s Writing on Human Rights–An International Literary Anthology – June 1, 1999

by

More that half a century after the United Nations Declaration of Human Rights, women throughout the world still struggle for social and political justice. Many fight back with the only tools of resistance they possess-words. A Map of Hope presents a collections of 77 extraordinary works documenting the ways women writers have spoken out about human rights.

Women writers, young and old, known and unknown, explore the dimensions of terror, the atrocities of war, and the possibilities of resistance and refusal in poems, essays, memoirs, and brief histories. The frequency graphic descriptions of the horrors of war, prison camps, exile, as well as political and domestic violence are counterbalanced with expressions of hope and confidence that a world of justice, harmony, and equality can be achieved.

Marjorie Agosin, an award-winning poet and human rights activist, presents here a global body of writings transcending national boundaries and ethnic identities. These are the voices of those who have decided to stand up against cruelty and injustice by appealing to the conscience of the world. Most of all, however, the writers in this volume put a human face on the profoundly dehumanizing experience of suffering the deprivation, especially as it affects innocent, noncombatant women and children.

Among the writers represented in this volume are Anna Akhmatove, Claribel Alegria, Isabel Allende, Sheila Cassidy, Nadal el Saadawi, Anne Frank, Nadine Gordimer, Hattie Gossett, Eva Hoffman, Barbara Kingsolver, Adrienne Rich, Nelly Sachs, and Aung San Suu Kye.

This publication has been supported in part by Amnesty International, with a percentage of the profits to benefit Amnesty International USA.

Book Excerpt

By Mahnaz Afkhami In A Map of Hope: Women’s Writing on Human Rights–An International Literary Anthology/ Marjorie Agosin (ed.) / Rutgers University Press / May 1999

I am in exile. I have been in exile for fifteen years. I have been forced to stay out of my own country, Iran, because of my work for women’s rights. I recognized no limits, ends, or framework in this work outside those set by women themselves in their capacity as independent human beings. The charges against me are “corruption on earth” and “warring with God.” Being charged in the Islamic Republic of Iran is being convicted. There is no defense or appeal, although I would not have known how to defend myself against such a grand accusation as warring with God anyway. There has not been a trial, not even in abstentia, and no formal conviction. Nevertheless, my home in Tehran has been ransacked and confiscated, my books, pictures, and mementos taken, my passport invalidated, and my life threatened repeatedly.

My life in exile began at dawn on November 27, 1978. I was awakened by the ringing of the telephone. My husband’s voice sounded very near. It took me a while to remember that he was calling from Tehran. He had just spoken with Queen Farah who had suggested that I cancel my return trip from New York scheduled for the following day. The government was trying to appease the opposition by making scapegoats of its own high-ranking officials. Feminists were primary targets for the fundamentalist revolutionaries. I had recently lost my cabinet post as minister of state for women’s affairs as the regime’s gesture of appeasement to the mullahs. It was very likely, my husband was saying, that as the most visible feminist in the country I would be arrested on arrival at the airport.

I searched for my glasses on the table by the bed and turned on the light, still clutching the receiver. I looked out the window at the black asphalt, glistening under the street lights. It must have rained earlier, I thought as I listened to my husband’s voice, tinged with despair, yet somehow aloof and impersonal, as if this had little to do with him. Two months later when I would call to discuss the deteriorating situation and the need for him to get away, I would sound the same to him. The ties between a person and her home are such that even those nearest fear to intervene directly.

When I said good-bye I was wide awake but not clear-headed. What will I do here, I wondered. During the past few weeks my days had been spent negotiating with the United Nations’ lawyers the terms of an agreement between the government of Iran and the UN, setting up the International Research and Training Institute for the Advancement of Women (INSTRAW) in Tehran. Evenings had been spent in meetings with groups and individuals trying desperately to affect the outcome of events in Iran.

Now it was suddenly all over for me. I could not go back home. I was left with a temporary visa, less than $1,000 in cash, and no plans whatsoever. I crossed the small room and automatically turned on the television to the Reuter news channel. The moving lines of the news tape were a familiar sight. In the last few weeks I had spent many hours staring at the screen, following the latest news, waiting for the inevitable items on Iran. When I looked up, the sun was streaming through the room.

Where would I go, I wondered as I dressed. I remembered I had planned to buy a coat that day. “What sort of a coat?” I asked myself. What sort of life will I be leading and what kind of a coat will that life require? Who am I going to be now that I am no longer who I was a few hours ago? I smiled at my reflection in the mirror. Need there be such existential probing connected to the buying of a winter coat? Even though I was far from the realization of the dimensions and the meaning of what had happened to me, my identity was already becoming blurred. The “I” of me no longer had clear outlines, no longer cast a definite shadow.

For a decade I had defined myself by my place within the Iranian women’s movement. The question “Who am I?” was answered not by indicating gender, religion, nationality, or family ties but by my position as the secretary general of the Women’s Organization of Iran, a title that described my profession, indicated my cause, and defined the philosophical framework of my existence. On that November morning in 1978, I realized that an immediate and formal severance of my connection to WOI was absolutely necessary. In those days of turmoil, when the movement’s very existence was threatened, WOI did not need a secretary general who had become persona nongrata to the system and its opposition. I sat at the desk in my hotel room and began to write a letter of resignation.

During the next days I lived a refusal to believe, a denial of the event, an inability to mourn — a state of mind which for me continued for years to come. A flurry of activity related to making arrangements concerning the death is the surest means of keeping full realization of the fact of it at bay. So I plunged myself into a series of actions aimed at ensuring survival in the new setting. The first priority was obtaining permission to stay in the United States. You need this to get a job although sometimes you can’t get it without having a job — one of the many vicious circles encountered in the life of exiles. Those who enter the country as exiles discover that what had been their natural birthright at home will now depend on the decision of an official who may, for any reason at all or none, deny permission, a process from which there is no recourse.

As soon as possible, I was told, one must get the necessary cards — driver’s license, social security, credit card. These are to help one to assure the community that one exists and will continue to exist for the foreseeable future and can be trusted to handle a car and pay a bill. There is a certain excitement involved in all this. Finding a place to live, learning new routines, looking for a job, establishing new relationships — all within a separate reality, outside the framework of one’s customary existence. It is possible to once again ask, “What do I want to be?” I contemplated whole new careers, from real estate to law, from teaching to opening a small business. They all seemed equally possible yet uniformly improbable.

All of this activity buys one time — time to assimilate the fact of loss and time to prepare to face it. You are told often that you must distance yourself from the past, that you must start a new life. But as in the case of death of kin — you don’t want to move away, close his room, give away his clothes. You want to talk about him, look at pictures, exchange memories. You shun contact with all those healthy, normal natives who are going about their business as if the world is a safe, secure, and permanent place a piece of which belongs to them by birthright. You work frantically to retain the memory and to reconstruct the past.

When you mourn a loved one, you wish more than anything to be either alone or with others who share your sense of loss. I sought mostly the company of other exiled Iranians. Together we listened to Persian music, exchanged memories, recalled oft-repeated stories and anecdotes, and allowed ourselves inordinate sentimentality. We remembered tastes, smells, sounds. We knew that no fruit would ever have the pungent aroma and the luscious sweetness of the fruit in Iran, that the sun would never shine so bright, nor the moon shed such light as we experienced under the desert sky in Kerman. The green of the vegetation on the road to the Caspian has no equal, the jasmine elsewhere does not smell as sweet.

Like children who need to hear a story endless times, we repeated for each other scenes from our collective childhood experiences. We recalled the young street vendors sitting in front of round trays on which they had built a mosaic of quartets of fresh walnuts positioned neatly at one inch intervals. We recalled the crunchy, salty taste of the walnuts carried with us in a small brown bag as we walked around Tajrish Square, taking in the sounds and sights of an early evening in summer. We recalled the smell of corn sizzling on makeshift grills on the sidewalk. We remembered our attempts to convince the ice cream vendor, a young boy not much older than ourselves, to give us five one-rial portions of the creamy stuff smelling of rose water, each of which he carefully placed between two thin wafers. We knew that any combination of sizes would get us more than the largest — the five-rial portion. But the vendor, in possession of the facts and in command of the situation, sometimes refused to serve more than one portion to each child. We remembered walking past families who were picnicking, sitting on small rugs spread by the narrow waterways at the edge of the avenue, laughing and clapping to the music which blared from their radios, oblivious of the traffic a few feet away. We laughed about our grandmothers or aunts who sat in front of the television enjoying images from faraway places, around which they constructed their own stories, independently of the original creator’s intention.

We recalled all this with affection and nostalgia. Yet we cursed ourselves and our culture and our habits and expressed our distrust, contempt, and suspicion of our compatriots. “Iranians are …” began an enumeration of our supposed national characteristics, confirmed, reiterated, and further embellished by each person present, provided that they were all from the same background and that there were no outsiders among them. These descriptions did not include the revolutionaries, around whose character a new set of myths had begun to accumulate.

During the first year of the revolution, the hostage crisis dominated our lives. Each evening we waited for a news show called “America Held Hostage.” We watched with disbelief images of bearded, shouting, fierce-looking youth, brandishing machine guns and shoving blindfolded American diplomats in front of the ravenous television cameras that gorged themselves on these scenes, spouting them out every night on this and other programs, making it harder with each passing day to identify ourselves by our nationality in casual encounters on the street, in a store, or on a bus.

The next year brought a consolidation of the power of the clergy over the population and a systematic clamp-down on those they considered their enemies. Women were the subject of daily admonition, direction, or complaints in the government-controlled press of the Islamic Republic of Iran. Their dress, their manner, their duties at home and in society, their role as mother and wife, the danger of their seemingly irrepressible sexuality were discussed endlessly regardless of what calamity faced the country. War, famine, internal upheaval, international crises were each and all unable to push women off the front pages of the newspapers.

As months passed, women persisted in their novel and original methods of resistance. We heard and read how they let their veils slip back slightly off thei foreheads, covered their legs in stockings that were a shade thinner than prescribed, wore raincoats that were belted at the waist, sunglasses that not only covered mascaraed eyelashes but indicated Westernized tastes and ways. All indications were that women were by no means under control. They pierced the heart and conscience of the mullahs and their adamant followers with their persistent forays into the margins of proper behavior. Women who had never worn makeup before began to wear it as a statement of their independence. That the numbers of women who followed these patterns seemed to grow instead of diminishing was a source of constant anxiety and frustration to the government. We read with disbelief and amusement the president of the Islamic Republic’s declaration that the rays emanating from a woman’s hair disrupt the composure of males in her vicinity — a phenomenon which he declared a justification for strict enforcement of the veiling regulation. The statement was followed by many similar dictates from religious authorities. The newspapers proudly carried news of guards stopping women on the street to admonish them for poor coverage of their heads and bodies. We heard accounts of women being dragged off to be questioned and flogged. We learned of cases where lipstick was wiped off with a razor blade and the scarf was attached to its proper place on the forehead with a thumbtack.

The media were mesmerized as the Ayatollah Khomeini issued decrees of death and destruction against individuals and groups within Iran and individuals, nations, and whole regions without. Pundits who had knelt reverently before him in the village near Paris before he arrived in Iran continued their objective, neutral coverage of his statements of prejudice, cruelty, and megalomania. I, who had experienced the camaraderie and support of the international feminist community, was affected more than others by their silence during the first few years after the revolution. Even when pregnant women accused of adultery or those accused of homosexuality were stoned, even when Ms. Farrokhrou Parsa, Iran’s first cabinet minister for education, a doctor, teacher, feminist was executed on charges of prostitution, few commented. In fact, her execution did not even merit a mention on the evening news. The total absence of reaction or support made me begin to doubt my own perception of reality. Nearly a decade would pass before the announcement of the fatwa against Salman Rushdie once again would make it possible for Western intellectuals to have a clear-cut, strong reaction to Khomeini. The protest would come not on behalf of Iranian women, but in support of a British writer’s freedom of expression.

During the early years I kept myself frantically busy with phone calls, lectures, meetings. Slowly, the life I had fashioned for myself in the new surroundings began to take shape. I now had a home in a suburb of Washingtion, D.C. Artist friends helped me collect a small selection of the works of Iranian women painters. A growing library of my old favorite books of poetry and fiction found a place in my room. The Foundation for Iranian Studies, a cultural institution that I helped create and managed with the aid of former colleagues, began to expand its activities. My family survived the travails and threats against them and all gathered near each other around Washington. Iran as a physical entity grew dimmer in our memory and more distant. But we remained obsessed with the events and processes that had led to our exile. All conversations, social occasions, and readings centered around what happened to us and more often than not ended in assigning blame.

As I went about building a life for myself in America, I learned through many encounters to simplify the spelling of my name, to mispronounce it to make it more easily comprehensible for my new contacts. I made small changes in my walk, posture, way of dressing to approach the new environment’s expectations. In the process I drifted farther away from my self. The woman exclaiming about the weather to the sales girl at Macy’s, calling herself Menaaz was not me. The original word, Mahnaz, had a meaning — Mah, moon, Naz, grace. Translating myself into the new culture made me incomprehensible to myself. I barely recognized this altered version of my personality. Frost once said “poetry is what is lost in translation.” I realized that whatever poetry exists in the nuances which give subtlety to one’s personality is lost in the new culture. What remains is dull prose — a rougher version, sometimes a caricature of one’s real self. This smiling, mushy person was not me. It was my interpretation of the simplicity and friendliness of American social conduct. I embarassed myself with it.

In public places I acted as if I were alone. In Iran, even in places where I was unlikely to meet someone I knew, I always acted “socially” — as if the people I met were potentially people I might come to know, people I might see again. I conducted myself with a consciousness of this assumption of possible further acquaintance, of a reasonable continuity of events. In America I acted totally isolated and separate, as if there were no chance that someone on the street might ever related to me in any other way than as a total stranger. I caught glimpses of my American friends chatting with the owner at a restaurant in the neighborhood, greeting friends at other tables, talking about their plans, their homes, their professions, discussing the variations in the menu with the waiter, amazed that life went on as if nothing much had happened. I longed for this elemental sense of connection with my environment.

I kept on searching for the effects of dislocation on my feelings and reactions and spent much of my time studying my own mental state. The preoccupations had come close to neurotic proportions. Fortunately, in my work with the Sisterhood Is Global Institute, an international feminist think tank, I had become acquainted with a number of women from various countries who, like myself, were in exile. Gradually, through our conversations, I began to see that the only way to understand myself was to stand back from my own experiences and focus on someone else, that the best way to see inside my mind was to concentrate on another as she looked inside hers. It was in talking with them that I began to reappropriate myself.

My conversations with twelve of these women led to the publications of Women In Exile, a project that became a cathartic and healing experience for me. I learned through writing the stories that although my past was mine in the specifics of my experiences, I shared so much of its deepedr meaning with other women in exile. Working with the, I began to see the fine thread that wove through all our varied lives and backgrounds. The narratives all followed the same pattern.

Our stories begin with descriptions of a society’s disingenuous ways of shaping the woman’s personality to fit the patriarchal mold. Even those who are active participants in political movements are often outsiders withouth the power to influence the decision-making process in their society. Political events beyond our control lead to upheaval. We are vulnerable and as caretakers of families our lives are most affected by disruptive and cataclysmic events. There comes a time when our own safety or that of our children requires us to take charge of our lives and make the decision to escape. Many of us are forced to undertake journeys of turbulence and danger. Once in the United States we realize that the physical dangers we have endured are only the preliminary stages to a life of exile. Slowly we begin to absorb the full impact of what has happened to us. A period of bereavement is followed by attempts to adjust to the new environment. Along with the losee of our culture and home comes the loss of the traditional patriarchal structures that flouted our lives in our own land.

Exile in its disruptiveness resembles a rebirth. The pain of breaking out of our cultural cocoon brings with it the possibility of an expanded universe and a freer, more independent self. Reevaluation and reinvention of our lives leads to a new self that combines traits evolved in the old society and characteristics acquired in the new environment. Our lives are enriched by what we have known and surpassed. We are all “damaged,” but we repair ourselves into larger, deeper, more humane personalities. Indeed, the similarities between our lives as women and as women in exiles supersede every other experience we have encountered as members of different countries, classes, cultures, professions, and religions.

We appreciate the United States as a safe haven, a place which welcomes us and allows us to find ourselves. We appreciate the relative freedom of women in this society. We are, however, conscious that the country is hospitable for the young and for the strong. We fear the loneliness and fragility of the old and the weak in this country. We regret that we have lost the closer ties and more committed interpersonal relationships with the extended family we enjoyed at home. Yet we know that for women, part of the price of having those close ties is loss of independence and freedom of action.

In the years since exile began, for some of us, conditions in our home countries have changed, allowing [us] to return. Those who returned home discovered the irreversible nature of the exile experience even when it became possible to return. They realized not only that their country had changed but that they themselves are no longer who they were before they left. They learned that once one looks at one’s home from the outside, as a stranger, the past, whether in the self or in the land, cannot be recaptured.

We are aware that we have lost part of ourselves through the loss of our homeland. We find substitutes for our loss; for some work acts as a replacement, for others, language. We echo each other when we say the world is our home and repeat wistfully that it means we have no home. We talk of having gained identification with a more universal cause.

We have learned first hand that nothing is worth the suffering, death, and destruction brought about by ideologies that in their fervor uproot so much and destroy so many and then fade away, blow up, or self-destruct. We learned in looking back over our lives that nothing is worth the breach of the sanctity of an individual’s body and spirit. The sharing of our narratives of exile made us conclude simply that we wish to seek a mildness of manner, a kindness of heart, and a softness of demeanor. When has a war, a revolution, an act of aggression brought something better for the people on whose behalf it was undertaken? we asked ourselves and each other. We have paid with the days of our lives for the knowledge that nothing good or beautiful can come from harshness and ugliness.

Copyright © Mahnaz Afkhami

Book Reviews

From Publishers Weekly