The century just passed was marked by unprecedented violence and cruelty. Most nations suffered or contributed to war, destruction, and genocide, the most egregious of which– the two world wars and the Holocaust–began and occurred mainly in the West. Untold numbers were sacrificed at the altar of ideology, religion, or ethnicity. Innocent people were led in droves to destruction in various gulags–prisons large enough to pass for cities and cities confined enough to pass for prisons.

Women and children everywhere suffered most from violence not of their making, perpetrated against them in national ways, in ethnic animosities, in petty neighborhood fights, and at home. Many of us have lived most of our lives under the threat of total annihilation because mankind achieved the technological know-how to self-destruct. The end of the Cold War removed the immediate causes of wholesale destruction–but not the threat contained in our knowledge. We must tame this knowledge with the ideals of justice, caring, and compassion summoned from our common human spiritual and moral heritage, if we are to live in peace and serenity in the twenty-first century.

The promotion of a culture of peace requires more than an absence of war. In the past two hundred years most of the world lived directly or indirectly within a colonial system. This system reflected an increasingly divided world of haves and have-nots. The modernizing elite in the technologically and economically poor nations responded to colonialism by the “enlightened” optimism that spearheaded much of the humanism of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries is now yielding to a pessimistic view that we are losing control over our lives. We sense a growing cynicism engulfing our view of government and political authority. In the West, where modern technology is invented and domiciled, many people feel overwhelmed by the speed with which things both moral and material change around them. In non-Western societies, the inability to hold on to some constancy that in the past provided a cultural anchor and therefore a bearing on one’s moral and physical position today often leads to normlessness and bewilderment. In the West or East, no one wishes to become a vessel for a technology that evolves uncontrolled by human will. On the other hand, it is becoming increasingly difficult for any one individual, institution, or government to exert its will meaningfully, that is, to ethically mold technology to human moral needs.

This seemingly uncontrollable technology, however, will be a harbinger of great promise, if we agree on the shared values contained in our major international documents of rights, and if we adopt a method of decision-making that justly reflects our common values. After all, we have gained almost magical powers in science and technology. We have overcome the handicaps of time and space on our planet. We have uncovered many secrets of our universe. We can feed and clother the peoples of our world, protect and educate our children, and provide security and hope for the poor. We can cure many of the diseases of body and mind that were deemed scourges of humanity only a few decades ago. We seem to have passed the era of absolutes, where leaders assumed the right to incarcerate, slaughter, or otherwise constrain their own people and others in the name of some imagined good. We have the ability to achieve, if we master the necessary goodwill, a common global society blessed with a shared culture of peace that is nourished by the ethnic, national, and local diversities that enrich our lives. To achieve this blessing, however, we must assess our present situation realistically, assign moral and practical responsibility to individuals, communities, and countries commensurate with their objective ability and, most importantly, subordinate power in all its manifestations to our shared human values.

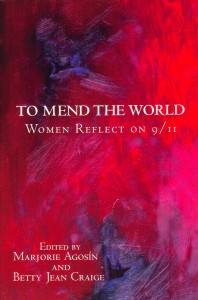

In To Mend the World: Women Reflect on 9/11, Marjorie Agosín and Betty Jean Craige (eds.) • White Pine Press, New York • 2002